Open Letter in Reaction to

La Paix Des Femmes

Maxime Holliday, Translated by Julia Thomas

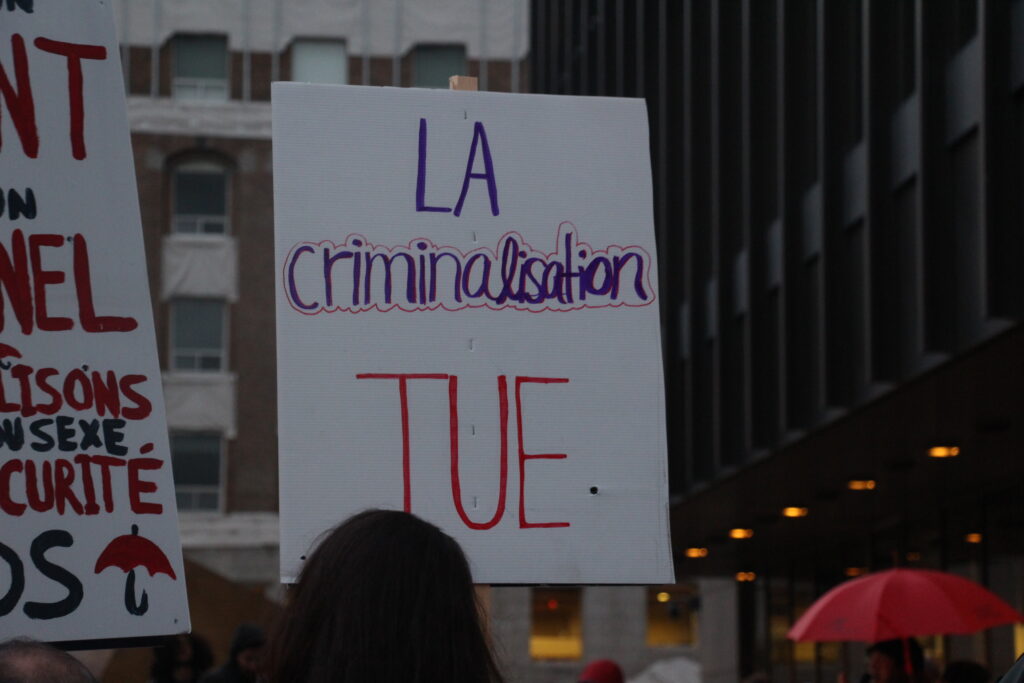

La paix des femmes is a play written by author Véronique Côté in collaboration with abolitionist activist Martine B. Côté. Together, they sign this work as well as a related essay (Faire Corps), both published by Atelier 10 editions. The play was presented in Quebec City at La Bordée in the fall of 2022. One month before the performances began, Maxime Holliday, activist from the Sex Work Autonomous Committee (SWAC), published this open letter to denounce the play which, according to her, makes a crude, alarmist and dangerous representation of sex work. Speaking directly to the author, Maxime called for more diverse voices from the community to be brought into the play, thereby attempting to clarify (again) the difference between consensual exchange of sexual services and sexual exploitation. Following the distribution of the letter, a dialogue between Maxime and Véronique led to the latter withdrawing a line from the play and proposing that part of the written exchange between the two women be printed and displayed in the theater hall. During the first performance, pro-sex work activists interrupted, standing and carrying red umbrellas, to chant “my work, my choice” before leaving the room.

Hi Véronique,

I’m writing to you today to discuss your play, La Paix des femmes. To start, I want to say I have much respect for your body of work – both the literary and the theatrical. You directed me twice during my time at CÉGEP, and I adored you. I will never forget when République: un abécédaire populaire came out, and you canceled our rehearsal to take us to the cinema to see it. I thought it was so beautiful, so rad, I promised myself I would always live up to the energy and passion you shared with us. I read S’appartenir(e) and La vie habitable. I saw you in Mois d’Août, Osage County and Laurier Station: 1000 répliques pour dire je t’aime. I went to see Scalpée because you were the director. I was never disappointed. You are right and you have a gift for touching people.

When I heard from friends earlier this summer about La Paix des femmes, I was excited. Because prostitution is a subject I’m passionate about and one that I know well. A little background on my life – after CÉGEP I did a bachelor’s degree, traveled, worked in restaurants and bars, and started playing music. I got a second college diploma and moved alone into a beautiful apartment with an old, adopted cat. During the pandemic, I meditated, worked on art projects, met a wonderful person with whom I share a deep, loving relationship to this day, and moved to Montreal. I ended my career in food service after being hostile with two customers in the same week. I was stretched to the max after eight years in the industry and knew myself well enough to pull back before I snapped. In 2021 I started working at an erotic massage parlour, which I still do today, as well as working from time to time as a nude dancer in bars. I love it. My life is balanced and dynamic. I am a curious, politically engaged, caring person. I make art with my friends, performances and I take care of myself, my family and those around me. I read Martine Delvaux and Judith Lussier and listen to Angèle Arsenault.

My friends are aware of my work in the sex industry, so I quickly heard about your play being published. I was told it was a dialogue between an abolitionist and a pro-sex-work scholar. I was told it was nuanced and written from multiple perspectives. I was skeptical but eager to read it because you wrote it. That is until my mother wielded your text at me to convince me to stop doing sex work. My poor, terrified mother, who has brutally invalidated me since I first wrote to her almost a year ago telling her about my work. My own mother, so freaked out that she can’t even hear or listen, much less trust me when I try to tell her about my experience. My mom emailing me your play. And my stomach in knots because, at that moment, I realize that the play confirms all her most sordid fears about my existence. At first, I’m so exasperated I tell myself I won’t read it. Anyway, she has refused to read anything I send her for a year. But what I needed the most was to be considered and heard. So I chose to open a dialogue by offering her a reading in exchange for a reading, which she eventually accepted.

So I read your play. While camping in the Jacques-Cartier Valley with my lover. I understand that your writing comes from a feminist impulse, a place of benevolent sisterhood, but I find this text hurts. Because it’s not a dialogue. It’s a lynching that rehashes all kinds of clichés about sex work in which exploitation, human trafficking and prostitution are all the same. The conversation occurs between a young woman (Alice) who decides to brutally confront Isabelle, the former feminist studies teacher of her sister (Lea), dead of an overdose six months after having started to prostitute herself. Alice blames Isabelle and the feminism she upholds for having caused her sister’s death, relying on an aggressive and dismissive abolitionist rationale. The character of Isabelle, who supposedly bears the pro-sex work argument, is discredited in the blurb on the back cover and tends to make dubious statements. She keeps waving “agency” as the solitary white flag to defend sex work in her discussions. And yet it is this same agency that we lose when she suggests that, as sex workers, “it is all we have left “1 and “they can’t take that away [from us].”2 Such claims strip sex workers of our agency, victimizing us and painting a bleak portrait of our reality. The story of Lea, dead after being recruited into a trafficking ring, inspired by the real lives of women who have been victims of coercion, extortion, abuse, and assault – is valid and alarming. We do need to talk about this reality, to denounce it. To shout out loud that as women in a misogynist and oppressive patriarchal system, we have lived and continue to live through appalling sexual violence. In this system, violence, as you say, is everywhere. It is intersectional. But I am so angry that these stories of exploitation are systematically used to represent prostitution in general, invalidating all those whose experience of sex work is ordinary or even straight-up positive. Ordinary experiences generally aren’t reported publicly or are labeled as isolated cases, creating an unbalanced and distorted image of our lives. Because If we are shown reports from Radio-Canada on “sugar babies” being manipulated and abused or women getting assaulted and killed, they also need to show us the story of the 45-year-old woman who has quietly worked for 20 years, and those for whom sex work is a means for empowerment and a good life.

Clarifying the difference between the consensual exchange of services and sexual exploitation, once and for all, would allow us to better combat pimps and fight to curb human trafficking more effectively. At the same time, SWers would benefit from improved working conditions to organize themselves and ensure their health and safety at work. Because this is indeed an intense job, and it is not made for everyone. The cliché of quick and easy money is totally absurd. Sex work is work. There are many security challenges, and strong relational, communication, and entrepreneurial skills are a requirement. It seems evident to me that all the energy used to discredit SWers and try to make them disappear would be much better used to help them obtain better tools for their trade and establish an empowering and safe social and legal framework. You infantilize a person when you suggest you are better at making choices about her life than she is. The worldwide abolition of prostitution is a legal and theoretical fable that only works on paper. I fail to see how the state could control the individual agency of SWers and their bodies without falling into repression and totalitarianism. And while it is indeed urgent to find ways to help women in extreme poverty who prostitute themselves to survive, it must be recognized that social and economic precarity would persist even if prostitution were made wholly illegal and/or magically disappeared. We can only make the lives of sex workers more difficult by stigmatizing them and working against them and their clients. Like with abortion, which can never be totally eradicated but can undoubtedly be dangerous when practiced under the wrong conditions, I believe that prostitution in Canada should be decriminalized 3 ; to allow SWers to self-organize according to their needs, which they know best, and create shared spaces, training opportunities, and unions to foster the improvement of their working conditions.

La Paix des femmes, unfortunately, still contributes to the deliberate conflation of consensual exchanges of voluntary sexual services with human trafficking. Because if I understand correctly, the play was written based on only two testimonials (K. and C., thanked at the end of the book)? It seems that a sample of two individuals is not enough to get an accurate idea of how a whole environment, which one has not directly experienced, works. The contribution of your friend Martine B. Côté, student researcher and abolitionist activist who has worked with victims of exploitation, was no doubt highly relevant. If the play, and the attached essay, claimed to be about exploitation and sex trafficking, that would be fine. But because the works claim to speak “for women and against the system that exploits them” 4 about the concept of prostitution in general, I find the gratuitously violent and shocking images conveyed in the play to be shamelessly ridiculous and crude. 5

It seems to me that this willingness to see using one’s body in a sexual way as automatically dangerous, painful, dirty, dishonourable, and shameful is a throwback to the outdated Catholic thinking that once controlled sexual morality. Suppose we believe today that women have a right to their bodily autonomy and sexual freedom. Why should “dislocating your jaw from giving blowjobs”6 (which already strikes me as either a horrible experience of sexual violence or a stylistic exaggeration but not a frequent consequence of practicing fellatio) be a worse scenario than destroying your lungs by breathing in chemicals in a factory, blowing out your vertebrae by lifting people to wash them in a hospital or ravaging your mental health as an overworked teacher in an elementary school? The patriarchal capitalist system exerts economic and social pressure and dominance on all women and all workers, regardless of their field. I am trying to demonstrate how our system threatens the physical and psychological health of so many of us. The working conditions of migrant people are often compared to modern slavery. The average household is being held in a chokehold by the ever-increasing cost of living. In this context, prostitution can easily be, for some people, the most practical and appealing way to pay for rent and groceries. It can also be an appealing occupation simply because sexuality and social work (because I assure you that sometimes we do act as social workers in lingerie) interest and stimulate us more than working in a hardware store, making sushi or being an administrative assistant in a production company.

For almost two years, I have worked with ordinary women, self-employed workers in the industry. Students, mothers, sisters, lovers, nurses, graphic designers, musicians, cashiers. For some, it’s a side job; for others it’s full-time. In the staff room, we tell each other our stories, we talk about our clients. Sometimes, we work on our computers in silence while waiting for appointments, sometimes, we share snacks and laugh loudly. In the strip club dressing room, we chat with the bouncer while putting on deodorant and take dinner breaks. We work where we choose to work and on good days, we earn a very good salary. I have many friends who work online, others who are independent escorts. I know a male escort for women too. Everyone, regardless of gender, needs physical contact. You’d be surprised how many people around us use these services but remain anonymous for fear of legal repercussions, stigma and shame.

Why is it still so inconceivable today that it is not necessarily humiliating and traumatic for a woman to get paid to dance naked or offer sexual services? Why is it automatically offensive to imagine a woman performing multiple blowjobs in one day? As far as I’m concerned, the end result of the feminist sexual revolution is to recognize the traumas we have lived through and to give ourselves the means, however diverse, to heal from them. Our great-grandmothers and grandmothers, required to sexually satisfy their husbands and produce children even when they didn’t want to. Our grandmothers, our mothers, and we live in a society where scientific research on female sexual organs is woefully behind that of male sexual organs. Our mothers, sisters, daughters, and we ourselves, who still have to research contraception for ourselves and fear that abortion rights will be revoked here too. Can we acknowledge our sexual trauma and work together to heal and liberate ourselves, all while respecting each other’s pace? Live and let live. I understand and appreciate that some women may feel repulsed and threatened by the kind of sexuality instilled in us by the hetero-patriarchal system. Because this model is indeed abusive, restrictive, and threatening to us. But all while recognizing this, could we also be capable of caring for each other inclusively and respectfully, allowing each of us the freedom to manage the use of our body as we see fit? If I enjoy offering sex, paid or free, with my own body, which I take care of and which belongs to me, who am I hurting? My body continues to belong to me after my workday. I ride my bike with it, I pet my cat with it, I eat with it, I listen to music that I like with it, I work out with it, I have a glass of wine with it. I have sold a service but not my body. I find that getting paid to perform femininity and heteronormative sexuality is also a way to infiltrate the institution to bring it down from within. Because it recognizes that women never owe men anything. No sexual and/or relational work. No care work and no extra mental workload. That there are people paid to offer this kind of service, as far as I’m concerned, contributes to a return of power. To avoid the exploitation insidiously victimizing all of us in societies that teach us to fulfill men’s needs for free because “it is due to them.”

Coming back to the play, I also want to mention the things I liked: first of all, the fact that it raises questions about bodily autonomy in the context of egg donation. This is a topic I knew little about until recently, and it is pertinent to reflect on. And secondly, I liked how the client archetype was humanized through the character of Max. Well, what I remember is that the couple doesn’t communicate very well and that Max betrayed his girlfriend. He’s not the hero of the story, let’s say. But I’ll take that as a jumping-off point to say a word about clients. Before working in the field, I thought clients would all be big drunk macho jerks or old perverts. In the end, those clients do exist, but they are not the majority. And just like massage therapists, osteopaths, or tattoo artists, after an unpleasant appointment with a bad client, I make a note to myself not to take that client anymore. In reality, the majority of my regular clients are ordinary people. Neuro-divergent people, people with disabilities, recently divorced dads, insecure young people, old widowers, veterans, terminally ill men, and newcomers who have difficulty meeting someone because of cultural and language barriers. People with human needs. People who want to cuddle, who want to come and be validated. The patriarchy harms male-socialized people too. Everyone needs to be educated and to heal. I believe in the capacity of people and societies to learn from their mistakes and to improve themselves. I think there are many ways to change people’s behaviour and stop exploitation and violence against women. But just as I don’t think banning the sale or purchase of sex teaches men to respect and care for women or themselves, I don’t believe that it is prostitution that prevents women from having the same privileges as men. Misogyny is everywhere. In the price of feminine-gendered products, fatphobia, systemic racism and rape culture. It is within our intimate relationships and marriages. It is in the justice system, deficient when it comes to defending survivors of sexual abuse. Violence exists far beyond the concept of prostitution, and I think the day that society respects and cares for prostitutes as for any other woman, we will all have won something.

You carry your feminist fight through your art, and so do I. There are many feminisms and truths, yes. But to read comments like Francine Pelletier’s, quoted at the end of your play, which suggest that women are being inconsistent by choosing “to look like dolls”7 or “choosing to stay home and raise their children”8 revolts me. To think that women cannot perform an ultra-feminine gender identity or decide to dedicate their lives to their children at the risk of harming the feminist cause is binary and outdated feminist thinking. It still puts all the pressure on women, as if society will always hold it against them no matter their choice. As for my feminism, I update it constantly, and I fight for it on all fronts. In my personal and professional life. On the streets, in my bed, and on social networks. My songs are about our emancipation, and I use my workplaces as a space for direct intervention. I work with my legs, armpits, hairy pubis, shaved head, and sometimes long nails and artificial lashes. I feel beautiful and whole. I always say what I think. I am gentle and tender, but I never overstep my boundaries: I am firm in enforcing them. I resist, educate, and I cum. Sometimes at work and always in my intimate life. I cum. Because I am a woman and I belong to myself. Because I am a rigorous intellectual, a passionate artist, a faithful friend, a committed lover, a staunch feminist, a caring sister and a gifted and proud sex worker. If I am accused of inconsistency, I would say it is more a matter of freedom. Cultivated and nurtured through adversity.

Reading your play, Véronique, I felt uncomfortable and bitter. It upsets me even more to think that the play will be presented in September at La Bordée. I can’t see how presenting this work will do anyone any good. But I can see how it will hurt many people. This play exudes fear, helplessness, rage, and pain but does not offer real solutions to improve anyone’s well-being. This play conveys all sorts of feelings that I share facing the injustices and violence experienced by women. Still, it approaches this complex subject in such a superficial and one-sided way that its impact is already being felt negatively in my personal life, as it will inevitably be felt in those of my friends and colleagues. Even if I do not share your opinions on the future of prostitution, I would like to highlight all the good you and Martine are undoubtedly doing by listening to and helping victims of sexual violence get out of violent situations and rebuild their lives. I sincerely thank you for being there for these women, but I also urge you to consider the impact a play like La Paix des femmes can have on the collective imagination. For if the three of us are initiated into the subject of prostitution and human trafficking, the average person is entirely ignorant of the reality and issues involved. To present such an alarmist and unnuanced work will have, in my opinion, damaging moral repercussions on the cause of SWers and women in prostitution, particularly in Quebec City and the surrounding area. Therefore, I am addressing this letter to you, Véronique, and the entire production team to ask you to act by opening a healthy and diverse dialogue with our SWers community and integrating other points of view and informative resources from our community into the presentation of your play. We really need safe working conditions, to be listened to, consideration, inclusion, justice and respect.

I am sending you this letter through the SWAC, a self-governed organization in which I am an activist, to maintain my anonymity. Thank you for respecting my anonymity, even though you may have recognized me by the very personal tone of my letter.

Thank you for reading my words.

In the hope of awakening reflection and compassion.

Maxime Holliday

25 juillet 2022

1. Véronique Côté. (2021). La paix des femmes, p. 90 ↩

2. SAME ↩

3. Like in a certain area of Australia, in New-Zealand and in Belgium since June 2022. ↩

4. Véronique Côté. (2021). Faire corps, back cover ↩

5. I want to reiterate that I speak from my experiences and those of my colleagues and whore friends. I am in no way discrediting the experiences of the women who have spoken to you, which are also very real and valid. ↩

6. Véronique Côté. (2021). La paix des femmes, p. 90↩

7. Francine Pelletier. (2018).Le corps d’une femme, Le Devoir quoted in Véronique Côté. (2021). La paix des femmes, p. 127 ↩

8. SAME ↩