The Power Wielded by Cities: Striving for Local Resistance

By Celeste Ivy and Melina May

Translation by Adam Hill

The criminalisation of sex work falls under “Canadian” federal jurisdiction, but the criminal code’s Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act is applied by law enforcement, judges, and tribunals of the Canadian provinces. It is also this set of laws that allows for the setting up of victim rescue projects across several territories. In 2014, when the law had just been passed, Harper’s administration pledged 20 million dollars to the fight against human trafficking; a bit less than a half would go to applying the law and the rest to agencies and organizations providing services to those wanting to leave the industry.

Although cities do not have the power to directly criminalize sex work, several municipal governments and district councils seek to control and limit certain aspects. In this article, we want to expose the power that cities wield over our working conditions. We also want to propose local organizing among SWers: a fight within our neighborhoods and our cities would allow for forms of resistance that are more direct, decentralized, and spontaneous. We will set out examples of repressive municipal regulations in Montreal, Laval, Toronto, and Edmonton: zoning regulations that threaten to make our spaces of work disappear, mandatory licensing in certain cities, and consequences of this on SWers’ integrity and security. We will also explore the birth and implementation of John Schools in Canada, presented as an alternative to the current criminal model that targets a particular demographic of clients. We will conclude by putting forward several strategies of organization and local action.

Urban Zoning: a Constant Threat to our Workplaces!

Increasingly, municipal governments are making use of zoning and urban planning regulations in order to target and shut down our workplaces. Although these regulations are formulated as if designed to guard against public disturbances and to ensure public health and security, we maintain that their aim is rather to undermine the working conditions of SWers and to “sanitize” cities of troubling, visible prostitution. This strategy also contributes to the larger process of gentrification.

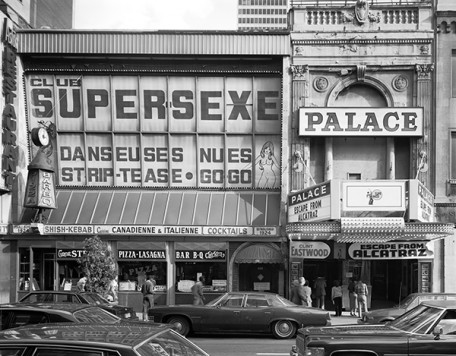

During the 2007 Rendez-Vous Montréal Métropole Culturelle, the city of Montreal and the Ville-Marie district presented the Programme particulier d’urbanisme du Quartier des Spectacles as the outline of plans for the urban renewal of Place des arts. The primary motivation of the urban transformations initiated by this program was to visually sanitize the Quartier des spectacles, historically the Red Light District, center of Montreal’s entertainment and sex work, supposedly with the aim of reviving a “dead” neighborhood. These attempts at clearance date back to the 1950s, when the then mayor Jean Drapeau launched multiple political campaigns and urban renovation projects aimed at revamping the neighborhood.There was a distinct irony in the political discourse that claimed to want to make Montreal a more lively and cultural city: the Quartier des spectacles was already a cultural center, but in a form that the municipality preferred to erase. Confronted by the literal destruction of their place of work and increased street-level surveillance, SWers were forced to relocate to neighborhoods where their presence would be less visible to the authorities and where finding clients would be more difficult.

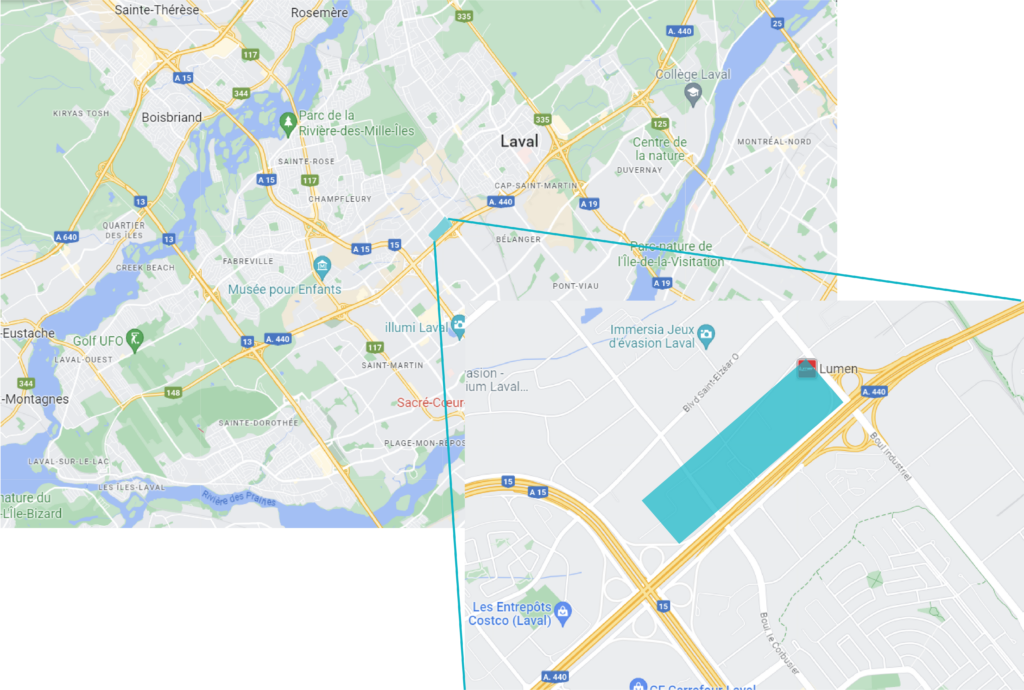

Among the tactics adopted by district councils and municipal governments, the tightening in the issuance of business licenses has proved effective in closing massage palours and strip clubs. In Montreal, this strategy formed part of the electoral promises of Coderre’s administration when he came to power in 2013. If this tactic was not successful, several districts of Montreal have, since then, adopted measures to get rid of massage parlors in their neighborhoods. Since 2017, the Rosemont-La-Petite-Patrie district no longer grants commercial occupancy permits to businesses suspected of seeking to open erotic massage parlors. Following this decision, eight massage parlors have seen their business license revoked, forcing them to close down shop. This tightening of licensing was proposed by the mayor of Projet Montréal, which goes to show that the erasure of our workplaces is a project that rallies the left as much as the right. In September 2023, the district announced their intention to pursue legal proceedings up to the Superior Court in order to shut down the last erotic massage parlor in their jurisdiction, Spa Bamboo. This parlor had appealed the decision in 2017 and continued its activities. In Laval, since 2018, massage parlors and strip clubs are banned across the whole jurisdiction except within the industrial zone at a maximum of five establishments, which are not allowed to display any signage or advertising. Such municipal measures explain the disappearance of clubs across Quebec at large: fifteen years ago there were 220 establishments in the province, now there are no more than 60. In Toronto, the Division of Municipal Licensing & Standards allows only 63 adult entertainment licensing in its jurisdiction since the 1970s. Zoning laws and the procedure for applying for an exception, which costs between $100,000 and $250,000, make the opening or relocating of these clubs almost impossible.

We have all met a SWer who dreamed of opening their own establishment, offering better working conditions and increasing inclusivity, but the stubbornness of this municipal sanitizing prevents the industry from developing ethically. Andrea Werhun, author of the memoir Modern Whore and social worker at Maggie’s, a pro-SWer activist project in Toronto, speaks to this same point:

I dream of a world where women or people who are sex-worker allies are running these clubs, and creating the type of environment where people feel both entertained but also fulfilled on a meaningful level, where they’re like, ‘Oh, this is just, like, a really great entertainment complex where people are enjoying themselves’

If these measures undermine the owners of clubs that already exist, the opening of new clubs by a woman or allies with fewer resources and administrative connections is basically impossible, which is in itself anti-feminist.

Cities make use, therefore, of their zoning and urban renewal powers in order to close our workplaces and to push us further and further from city centers towards industrial neighborhoods, which are less well-lit and more isolated. The decrease in the number of our workplaces and their lack of regulation also increases competition between employees and the power held by employers. An activist with SWAC and dancer explains the following: “Dances at my club are still priced at $10 because there are not many strip clubs and the managers let anyone come in at any time, which means there are so many girls on the floor and so much competition.” The closure of massage parlors and strip clubs will not put an end to the need to work for many. Forced out of our workplaces, many of them will turn to working from their home or outcalls. This further isolates us and puts us at greater risk of assault.

Licenses to Work: a Means to Control and a Threat to Security

In certain Canadian cities and provinces, for example Ontario and Edmonton, SWers in lawful spaces need to obtain a license in order to prove their age and work in a massage parlor or strip club. Although these licenses serve, inter alia, to inhibit access for minors to these spaces, they are also a means to control, weaken, and surveil SWers.

In May 2022, the city of Newmarket in Ontario adopted a new classification of licenses for massage parlor employees in an effort to curb the sex industry. As a result of the new measure, owners are obliged to prove that employees offering massage services received training at an accredited institution. The city’s mayor explained this decision as follows: “I think we really just want to drive [the sex trade] out of our town, quite frankly, […] I don’t think it’s consistent with the values of our town.”

A petition launched by Butterfly, an organization that defends the rights of migrant and Asian SWers in Toronto denounced the measure as “perpetuat[ing] systemic racism and undue hardship by preventing non-English speaking, low-income, Asian women from working in [personal wellness establishments]”. Following this decision, several businesses were forced to close overnight leaving many women and families without means of subsistence.

In Ontario, dancers are also required to obtain a license to work legally. SWers with criminal records and im/migrant SWers without permanent residency cannot apply for this license, which pushes them into work situations that are all the more precarious and criminalized. In Edmonton, massage parlor and agency employees must also obtain a license to work. Even if the physical copy of these licenses do not include any personal data, this data can nonetheless be accessed by employers, which threatens the integrity and security of SWers. In an open letter to the city hall, ANSWERS, an organization that defends the rights of SWers in Edmonton, denounced the harmful effects of such a measure: there are many cases of employers and/or colleagues disclosing sensitive personal information to SWer’s family, civil employer, or landlord. The obligation to share personal information with employers is not only dangerous, it is also redundant because SWers receive payment directly from clients.

The stigmatization experienced by SWers is also anchored in the introduction of work licenses; they are treated as a danger to public health. These licenses are a way for municipal officials and police to control SWers more effectively, without concretely offering support services for risk reduction or for safe working conditions. These forms of legislation are born out of a vision that is anti-SWer, in which SWers are perceived as a threat to public health and therefore need authoritarian surveillance. Those SWers working within the majority of legal contexts conform to standards set in place by the employer. This undermines the possibility of unionizing since the autonomy of SWers is heavily restricted and any consideration of working conditions is pushed further to the side. The actual needs of SWers in terms of their general security, harm reduction, and the improvement of their working conditions are ignored.

John Schools: a Moralizing Boot-Camp

In May 2022, the city of Longueuil put in place a pilot project financed by the Ministry of Justice designed to entrap clients and impose reeducation upon them by way of John Schools. Clients that were arrested by the police for the first time would have to pay $1000 and commit themselves to an eight-hour long course during which multiple speakers would lecture them and explain to them the dangers of the sex industry. The former police chief of Longueuil and current head of the Montreal City Police Service, Fady Dagher, explained how the course plays out: the clients come face-to-face with a young victim who explains to them “how she feels abused, […] how many drugs she has to take to get through her day, and how times she faked [an orgasm].” These programs refuse to consider SWers as actors in their own story. The offensive discourse that they expound foregrounds the popular narrative according to which SWers are passive victims that need saving, all whilst being presented as alternative justice programs.

The John School concept emerged in the 90s in San Francisco. The proponents of these programs defend them as an alternative to the punitive criminal model that remains ineffective, supposedly redirecting clients in a different direction. These programs can take several different forms, but at their core they offer the following choice to clients who have been arrested: commit to a day-long course or go before the tribunal, which would mean the risk of being found guilty and being given a criminal record. The programs are also designed to handle as many offenders as possible outside of the traditional system and therefore at the lowest possible cost.

The first John School in Canada dates back to 1996 in Toronto. Around this time, a growing number of citizens, concerned for their security and quality of life, began to put pressure on politicians, legislators, and the police to take action on street prostitution in their neighborhood. In 1995, a local committee on prostitution was formed, consisting of police officers, social workers, and local councilors. The setting up and running of the first John School pilot project was taken on by the Salvation Army, which is, unsurprisingly, also involved in probation and conditional release programs for the Canadian penal system. Originally, participation in the program was free, clients were invited to contribute via donations to an exit program for street-based SWers. Since the donations were insufficient, the Streetlight Support Services agency took over administrative control of the John School program, and introduced a mandatory participant registration fee of $400, of which 100% of the profits went to supporting the administration and mission of the agency.

These programs targeted and controlled a certain type of client: “the men diverted to the ‘John School’ tend to be working class, visible minority and English as Second Language (ESL) immigrants with comparably low levels of education and income levels.” It would be factually inaccurate to suggest that this is a representative cross section of men that pay for sexual services in Canada. Instead, it seems clear that John Schools serve to punish a certain fringe of the industry’s clientele, those from poorer and more marginalized socio-economic groups.

Certain programs in Canada are still supported today by Christian associations such as the Salvation Army. This non-profit organization, renowned for its murky past and homophobic practices, now has the power to interfere with the sex industry, extracting profit from it and exercising forms of control. These programs use moral panic about human trafficking to distract attention from the actual needs and concerns expressed by SWers themselves.

These programs have nothing close to do with restorative justice, as some current programs claim to defend themselves. Instead of offering an alternative to the criminalization of sex work, the John School model expands the scope of control and surveillance of sex work to non-governmental agencies.

For Workplaces Without Police: Local-level Resistance!

Keeping track of municipal politics becomes extremely important, even in the ideal context of decriminalization, because they constitute one of the principal regulatory mechanisms that govern the lives of SWers. A good example of the reach of their power is the city of Campbell River, which, several days before the start of the three-year pilot project that decriminalized the possession of drugs in British Columbia, adopted a new municipal regulation that sought to impose a fine on those who consumed drugs in public spaces.

In the face of constant threat from city governments, we must reflect upon strategies that can be put in place to protect our workplaces. In an extensive study of working conditions among dancers in the United Kingdom, the authors concluded their article by highlighting the potential that the granting of business licenses could have on defining workplace standards in the sex industry. According to Lo Stevenson, “[i]f these standards were negotiated with organized sex workers, adequately reflecting their needs and concerns, such a regime could not only increase autonomy and solidarity for sex workers, but also reduce reliance on costly and time-consuming litigation.” Putting pressure on local and licensing authorities, for example during city council meetings, to demand that business permits accord with our wishes or to block attempts by city governments to close our workplaces, could represent an interesting means of action.

Profiling, particularly of Asian women, during the inspection of massage parlors is a well-known tactic. In solidarity with our migrant colleagues who face constant targeting by the police, we should demand that the city of Montreal as well as the multiple other sanctuary cities in Canada make good on the commitments they have made towards those with this status and cease their collaboration with border services deporting SWers whether or not they have legal status. In Montreal, the collaboration between the police and Canadian Border Services Agency makes recourse to the protection of the police next to impossible for migrant SWers who are victims of criminal acts and abuse.

Although public health arguments are often mobilised to defend the criminalisation of sex work, we believe that decriminalization could support the reduction in the transmission of illnesses transmitted sexually or through the blood. In the current context in which clients are considered to be criminals, it is difficult for SWers to gain the necessary information from their clients, because they are even more reluctant to go through a filtering process generally put in place by SWers. Communication with our clients, not tarnished by fear of the authorities, would significantly help reduce risks for both parties involved. If clients could share their personal information with less fear of arrest, SWers could better choose their clients. This is why the Canadian municipalities involved must bring to an end the application of the federal law that criminalizes the sex industry as well as their punitive John School programs. The resources this would free up should be reinvested in community organizations that offer support and harm reduction services directly to SWers.