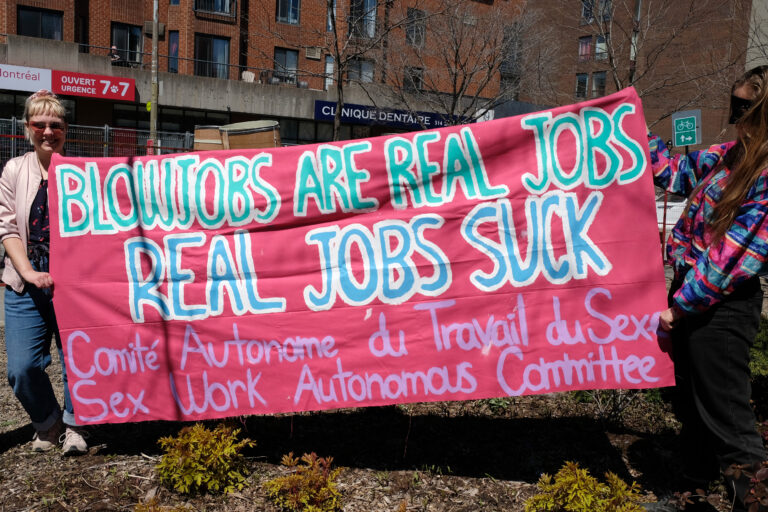

Montreal, Whoreganize !

Sex Work Autonomous committee

Invitation flyer for the very first SWAC meeting (page 1-2)

Autonomous from who and why?

Since our first calls to organize, one question has come up over and over again: “Why create a new organization when there are already community organizations to defend our rights? Aren’t they the best ones to speak for us with many years of experience?”. Let us first establish that the creation of autonomous committees is in no way intended to replace or eliminate any organization or to criticize particular individuals. However, we believe that discussions about the organizational models and structures that are in place in a movement can only be beneficial to the struggle. By creating an autonomous committee, we want to create a space where mobilizations and collective actions are priorities; we believe that we and our colleagues have much to gain by organizing politically. Since their inception in the 1990s, Canadian SWr organizations, like many others, have always tried to find a balance between providing services and collective action for political change, both at a legislative and public health level. Discussions on the tension between service provision and collective action have been a recurring theme in our conversations at SWAC over the past year. Time and energy being limited resources, we believe that asking this question early in the formation of a political group is essential. “This debate was already present at the founding of the Canadian Organization for the Rights of Prostitutes (CORP) in 1983” says Danny Cockerline, a gay activist, sex worker and founding member of CORP:In its early days, the CORP devoted all its energy to lobbying politicians, governments, the media, police forces, etc. in order to obtain their support for the decriminalization of prostitution. In 1985, Peggie and Chris formed a group to start a self-help project. The idea was that the CORP would only succeed if more prostitutes became involved, and only when their basic needs were met would they be able to devote time to political work.3

This new project was called Maggie’s and is still active today in Toronto. However, the idea of creating new services divided those involved at the CORP, according to Cockerline, since “many feared that they would end up with another social service that prostitutes would turn to for help rather than join us in creating an advocacy movement”4. Since then, the CORP has ceased its activities and Maggie’s continues to offer services. However, the initial idea of being a training ground for SWrs to mobilize is less and less present in SWr organizations. Sarah Beer, a researcher on SWr rights in Canada, is critical of this model:Funding formalizes organizational structures but tends to bureaucratize mobilization. The outreach services [recrutement practices of these organizations] that are provided can be restricted based on funding criteria (e.g., funding might give money only to do street-based, not indoor, outreach). […] As a consequence, sex workers need to organize on multiple fronts.5

Like Sarah Beer, we believe that if political demands and collective actions are not given priority in the SWrs’ rights organizations, it is because of the requirements of these structures, starting with those of their funders, and the resulting bureaucracy: activity reports and accountability, funding requests, action plans, human resources management and all the administrative paperwork that comes with them. In short, it is not surprising that there is not much time left to mobilize those who aren’t already active! The first SWr organizations’ funding was granted as part of the fight against HIV6. Of course, one can empathize with the fact that at the time, SWrs, like LGBTQIA+ populations and drug users, wanted to create their own health services to fight against an epidemic that was decimating their communities to the government’s disregard. However, as Act-Up activist and writer Sarah Schulman points out, these organizations are often reappropriated by governments to contract out work at a lower cost:The distinction between service provision and activism has become elusive. Poor people are very interwoven into state agencies: there’s a lot of surveillance […]. My life has shown me that activists win policy changes, and bureaucracies implement them. In a period like the present where there is no real activism, there are only bureaucracies.7

The bureaucracy of community organizations makes it difficult to have wide spaces to discuss solutions and to mobilize to defend our rights. This is why we believe it is time to organize on an autonomous basis. The foundations of such an organization still need to be defined. This is what we will try to do here. Of course, this is a work in progress and these principles are bound to be updated. It should also be noted that SWAC activists have varying perspectives and work experiences. These principles therefore serve as a basis of unity, first at a theoretical and then at an organizational level.

Invitation flyer to the very first SWAC meeting (page 3-4)

Theoritical principle:

-

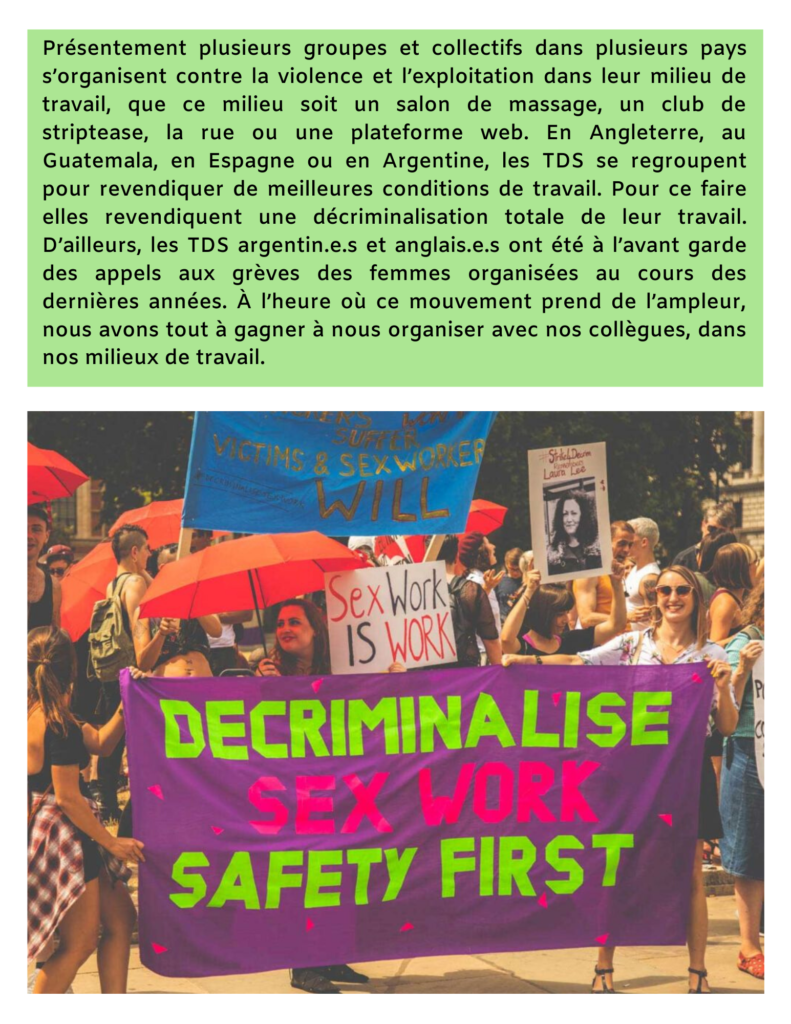

- The recognition of sex work as work and the need to decriminalize it in order to obtain the same labor rights as other workers;

2. The recognition that sex work takes place within a capitalist, neo-colonial and cishetero-patriarchal system; the recognition that women, racialized people, trans/queer/gender non-conforming people, migrants and people with disabilities are over-represented in sex work, due in part to the barriers to employment and good jobs in the capitalist system;

The context in which sex work takes place is often ignored by those who are outraged that women are forced to “sell their bodies”10. Instead, we start from the principle that all workers sell their bodies – this is a more interesting starting point in the struggle for better working and living conditions. In other words, starting from the point of view that work should be empowering and free from exploitation seems to be a trap to avoid. The sex industry, along with many others, is filled with exploitation, sexist and racist violence. However, few of us are in a position to refuse this work individually, because the reality is that we have to put bread on the table and pay the rent. Most of us are SWrs because it is the best or the least bad option available to us in this context. We have seen it throughout the pandemic; in Canada, statistics show that job losses have impacted women more severely than men11. In the United States, reports show that Black, Indigenous and Women of Colour are 1.5% more likely to lose their jobs because of COVID than white men older than 20 years old12. In Canada, BIPOC people still have a higher unemployment rate than White people, particularly Indigenous women13. This is also true if you are experiencing employment’s discrimination, whether you are a BIPOC, trans or disabled person. The job market is stratified by class, race and gender and it’s no coincidence that these people are over-represented in sex work. In this context, what options are available to SWrs who wish to leave the industry? Finding themselves behind the cash register of a grocery store or joining a long-term care facility to provide care? Not only do these options not reduce the risk of being exposed to the virus, but the expected decrease in income means that they’ll have to work even harder and lose time flexibility. This flexibility is desired and even vital for many, including, single mothers, students, and those with disabilities or chronic illnesses. Moreover, these work alternatives, often precarious and poorly paid, are not exempt from exploitation and violence. We also live in a time where an international division of labor prevails. The conventional definition of the international division of labour refers to the displacement of industrial production from the countries of the North to the countries of the South, where workers’ wages and protections are lower. Feminist thinkers have also demonstrated the importance of the work exported from the countries of the South to the countries of the North, particularly women’s reproductive work14. This can be seen by the large proportion of so-called essential work performed by migrant women, particularly in hospitals, daycare centers and long-term care facilities. These jobs are often done through employment agencies, causing a deregulation of work and allowing employers to get away with offering poor working conditions. More often than not, they are temporary jobs occupied by those with precarious immigration status, putting the people who work there at risk of deportation, as highlighted by the movement of migrant workers during the pandemic15. Similar logic applies in the sex industry, particularly in stripclubs, where female workers are often considered self-employed rather than employees. However, it is often assumed that women who migrate and work in the sex industry are victims of sex trafficking. This discourse ignores the role that borders and migration policies play in this process. Indeed, many are forced to accept terrible working conditions because of their precarious migratory status, but this reality is not specific to the sex industry, as some anti-prostitution organizations suggest.

Organizational principles:

-

- The self-representation of SWrs and their right to talk about their own realities, and non-hierarchical self-organization that allows the implementation of direct responses and actions;

-

- The mobilization of our colleagues in our workplace is the basis of organizing towards better conditions;

-

- Autonomy from government institutions and other institutional donors.

The crisis: an opportunity to reinvent the struggle!

The current crisis is an unavoidable moment of restructuring. The pandemic isolates us and makes us precarious, but it may also be an opportunity to reinvent our movement and organize ourselves, as it was the case with the HIV epidemic. While we recognize all of the barriers to mobilization, it’s time to be creative and to rethink our strategies.

1. Axel Tardieu. (2020). Elles posent nues sur Internet pour payer leurs études, ICI Alberta, https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1762202/etudiants-onlyfans-internet-pornographie-chomage?fbclid=IwAR1rDnzlEP5kVJ8s57jkyzS2XGsIutnbBi2xQXOWR21o4nTi2kBHwxgFOV4 ↩

2. SESTA (Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act) and FOSTA (Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act) are two bills passed in the United States in February and March 2018, supposedly aimed at combating sex trafficking. Under these two laws, web platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Craigslist, Backpage can now be charged with sex trafficking for published content. Thus, overnight, hundreds of SWrs have seen their income and security threatened by the closure of web spaces. Several SWrs also denounce that platforms like paypal or even their bank close their accounts without warning when they discover their activities: Jesse and PJ Sage. (2020). Episode 78: Porn Performers Talk Pornhub and Payment Processing, https://peepshowpodcast.com/episode-78-porn-performers-talk-pornhub-and-payment-processing

In December 2020, following a sensationalist article in the New York Times exposing the presence of underage videos and non-consensual acts on Pornhub, Visa and Mastercard stopped supporting payments on this platform. Several SWrs have denounced the fact that this measure will not affect the adult entertainment giant, basing its revenues exclusively on advertising, but will directly affect the revenues of those who sell their content on this platform. The links between the anti-Pornhub campaign and the American religious right wing have also been strongly denounced by journalist and ex-SWr, Mélissa Gira Grant. For more information: Melissa Gira Grant. (2020). Nick Kristoff and the Holy War on Pornhub, https://newrepublic.com/article/160488/nick-kristof-holy-war-pornhub ↩

3. Since we couldn’t find the original version, this quote is translated from the french version of this text in Danny Cockerline, «Whores History: A Decade of Prostitutes Fighting for their Rights in Toronto», Maggie’s Zine, n 1, hiver 1993-1994, Toronto, Maggie’s: The Toronto Prostitutes’ Community Service Project, p. 22-23. Traduit de l’anglais par Sylvie Dupont, dans Luttes XXX, Inspirations du mouvement des travailleuses du sexe, 2011, Les Éditions du remue-ménage. ↩

4. Idem ↩

5. Sarah Beer. (2018). «Action, advocacy and allies: Building a movement for sex workers right», Red light labor: sex work regulation, agency and resistance. p.332 ↩

6. In Montreal, Stella was born out of a consultation committee of the Centre d’étude sur le SIDA on which the Projet d’intervention auprès des mineurs prostitués (PIAMP) and the Association Québecoise des travailleuses et travailleurs du sexe (AQTS), among others, sat. The project was intended to be a sister organization to Maggie’s, which had received its first funding a few years earlier from the City of Toronto’s Public Health Department. Claire Thiboutot. (1994). Allocution: appui au projet Stella, Montréal, Association québecoise des travailleuses et travailleurs du sexe (AQTS) et Danny Cockerline, «Whores History: A Decade of Prostitutes Fighting for their Rights in Toronto», Maggie’s Zine, n 1, hiver 1993-1994, Toronto, Maggie’s: The Toronto Prostitutes’ Community Service Project, p. 22-23. Traduit de l’anglais par Sylvie Dupont dans Luttes XXX, Inspirations du mouvement des travailleuses du sexe, 2011, Les Éditions du remue-ménage, p. 48 à 52 ↩

7. Sarah Schulman. (2012). The gentrification of the mind: witness to a lost imagination. p. 16 ↩

8. See Wages for Housework. (1977). «Housewives & Hookers Come Together», Wages for Housework Campaign Bulletin, vol. 1, no 4, dans Louise Toupin. (2014) Le salaire au travail ménager, Chronique d’une lutte féministe internationale (1972-1977). Les éditions du remue-ménage, p.257 ↩

9. Idem ↩

10.The question of “selling the body” is a subject of debate even within the SWr movement. On one hand, it is defended that one does not really sell one’s body, but rather a service or one’s work force. The Girlfriend Experience is an example of this. On the other hand, it is argued that selling the body is present in every field, be it construction, professional sports or even office work, and that all of these jobs wear out the body in one way or another. This perspective also helps to understand how gender performance is expected in certain industries, such as the sex industry, catering or fashion for example. Whether one starts from one perspective or the other, sex work is not fundamentally different in this respect. ↩

11. Radio-Canada. (2020). 3 millions d’emplois perdus au Canada depuis le début de la pandémie, https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1701093/coronavirus-chomage-avril-canada-perte-emplois ↩

12. Catalyst, Workplace that Work for Women. (2020). The Detrimental Impact of COVID-19 on Gender and Racial equality: Quick Take, https://www.catalyst.org/research/covid-effect-gender-racial-equality/ ↩

13. Idem ↩

14. Sarah Farris. (2017). «Les fondements politico-économiques du fémonationalisme» dans Pour un féminisme de la totalité, Éditions Amsterdam, Période, p.189-210 ↩

15. Dan Spector. (2021). Quebec Curfew making life even harder for undocumented workers doing essential jobs: Protesters

https://globalnews.ca/news/7610014/quebec-curfew-making-life-even-harder-for-undocumented-workers-doing-essential-jobs-protesters/?fbclid=IwAR11NG9HO7itDYjSqwIUi-bClk2gY750KR4gcRPqVHZfGoMVmOql2B6eZS8 ↩

16. Strippers union United Voices of the World, Decrim Now. (2020). Strippers Union United Voices Of the World (UVW) Wins Landmark Legal Victory Proving Strippers Are ‘Workers’, Not Independent Contractors,

https://www.uvwunion.org.uk/en/news/2020/03/press-release-strippers-union-united-voices-of-the-world-uvw-celebrates-employment-tribunal-win/ ↩

17. Catherine Abou Al Kair. (2020). Livraisons : La condamnation de Deliveroo pour travail dissimulé peut-elle faire tache d’huile ?

https://www.20minutes.fr/economie/2717155-20200218-livraisons-condamnation-deliveroo-travail-dissimule-peut-faire-tache-huile ↩

18. CBC News. (2019). 300 GTA Uber Black drivers unionize as city mulls regulatory overhaul, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/uber-drivers-union-ufcw-toronto-1.5190766 ↩

19. To learn more : Haymarket Pole Collective. (2020). Press coverage, https://www.haymarketpole.com/press ↩

20. Tess Riski (2020). A Labor Movement Demands Better Treatment for Portland’s Black Strippers

https://www.wweek.com/news/2020/06/16/a-labor-movement-demands-better-treatment-for-portlands-black-strippers/ ↩