From Red Light to Quartier des spectacles

Cultural and creative industries, sex work, and gentrification

Interview by Maxime Durocher and Adore Goldman, Translated by Hannah Azar Strauss

AM Trépanier is an artist-researcher, editor, and cultural worker. Across their practice, they explore the particularities of different media, technologies, and actions to (re)mediate the discourse around a given situation. Their artistic practices take the form of publications, video, conversation, websites, and exhibitions. In their work, they pay close attention to the tactics used by marginalized communities and alternative publics to build new kinds of spaces, gain access to information, and appropriate various technical tools.

AM collaborated with the Sex Work Autonomous Committee (SWAC) as part of the project dans le souffle de c., which explores the processes of urban gentrification resulting in the re-purposing of a site dedicated to sex work into an imposing hub of artistic and cultural dissemination: the 2-22. We asked them to tell us more about their process and the discoveries of the research.

Adore Goldman (AG) and Maxime Durocher (MD): How did you become interested in the history of the 2-22?

AM Trépanier (AM): In the fall of 2021, I was invited to participate in a group exhibition reflecting from a critical perspective on the notion of value, beyond its definition by the market economy. The curators wanted to create a space that could present various postures taken by artists towards the institution of the economy.

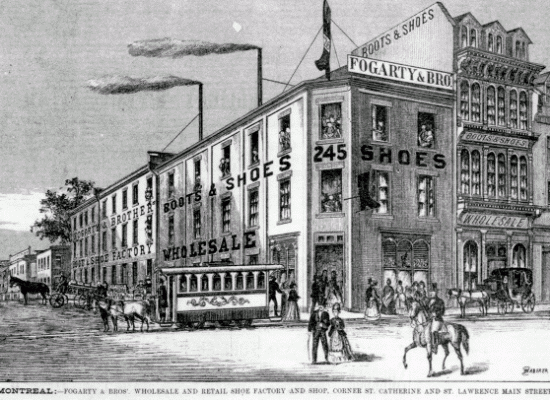

As a starting point for the project, I did some generic research on the history of the place where the exhibition is located: VOX, a center for the research and dissemination of contemporary images, is housed in a cultural complex called the 2-22, located at the corner of Saint-Laurent and Sainte-Catherine. While delving into the history of the 2-22, built by the Société de développement Angus (SDA) and inaugurated in 2012, I came across an image of the building that had preceded it there, just by walking around on Google Street View and observing the evolution of the street corner over time.

I was struck by the contrast. Before its demolition, the building on the corner was home to various small businesses right up until 2008, counting among them Studio XXX, an erotic cabaret that offered services like a peep-show and private booths for XXX movies and full contact dances. Basically, the building was primarily dedicated to the sex industry.

What immediately and organically came to mind was a desire to know what had caused such a transformation of the intersection. What forces had come into play to bring about this change in the neighbourhood, and who were the main actors in this transformation? What positions did these actors – the arts institutions, the media, the municipality, the real estate developers, the community groups, the state – occupy in the history of this “revitalization” of the neighborhood? And who benefits from this change?

AG-MD: When you did your research, what did you discover about the consultation process in terms of the transformation of this area? Were there stakeholders who were for or against the demolition and the new project? How did this process unfold?

AM: All I found in the City of Montreal’s Archives about the demolition of the old building was a resolution passed in 2006 at the City Council to expropriate (with compensation) the tenants of the building of which Studio XXX was a part. There was apparently no publication consultation on the demolition.

However, since the initial project of the 2-22 proposed the construction of a building exceeding the height limit allowed by the Urban Plan of the City of Montreal, there had to be a public consultation in order to get the necessary authorization before proceeding. It was at this time that the different interests of the people and organizations implicated could be identified. The various stakeholders were very divided.

In general, arts and culture organizations, especially those involved in the project and who would gain access to the property through the 2-22, were absolutely supportive of its development. It would provide security, access to a work and dissemination space almost impossible to find otherwise. This is a real issue in the arts and culture community, there’s no denying it. Access to space is very difficult to find for artists and distributors, who have not been spared by the rent increases related to gentrification. So having a permanent venue in the middle of the Quartier des spectacles was very attractive for organizations like VOX.

On the other hand, heritage and community organizations were less enthusiastic about the project. Heritage organizations were concerned that the SDA’s projects would not integrate well with the historical character of the neighbourhood, especially the sister project of the 2-22, the Quadrilatère Saint-Laurent [today known as Square St-Laurent]. This second component notably threatened to do away with Café Cléopâtre, but they resisted and refused to be expropriated. The case made its way to court.1

Many community organizations opposed the project or voiced reservations – because there is important nuance to this: organizations recognized that there was some value in the project, but they also saw risks, primarily for neighbourhood residents. Several organizations, like Stella2, wrote a brief to express their concerns.3

Essentially, what they proposed was to be a key stakeholder in the project, to be local actors in the building project of the 2-22, to have a say, to participate in the development of the project, to be consulted. They extended a hand to the project developers, but it was not well received.

Stella had been on the Main for eight years and so knew the neighbourhood very well. What’s more, they had been among the many people and organizations who had to relocate due to poor building conditions. They recognized that it was a neighbourhood that needed care, love, money, and development, but not in the way proposed by the SDA, the company executing the 2-22 project.

Another thing that I learned reading the brief from Stella was that during the time that they were located on Saint-Laurent Boulevard, they had a display window and organized exhibitions, mainly about sex work and the history of the Red Light district.

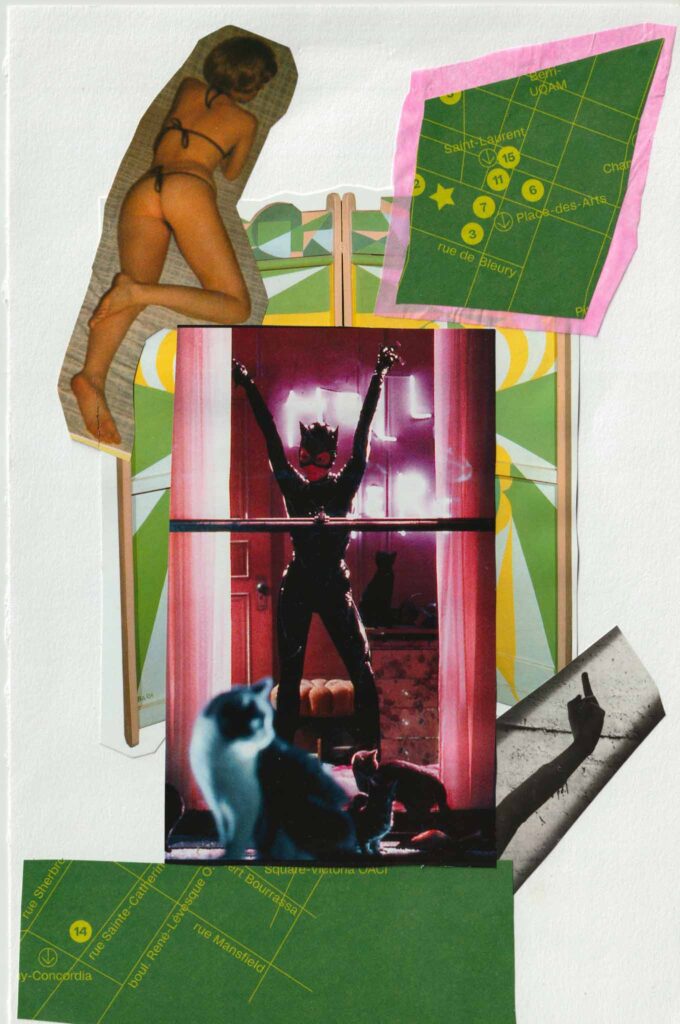

This highlights an important question when we’re talking about cultural policy: what is defined as belonging to the cultural sector, and what kind of practices are given visibility? For example, material related to sex work, like the window exhibitions presented by Stella, would not so easily be found on the walls of the 2-22 because the “guardians of culture” have judged it immoral. This is evidenced by the bylaws of the building. They are not welcome in exhibition spaces, in spaces of cultural diffusion, because for some, these forms of expressions are taboo. But with the choice to avoid offence, we push them to the margins. It’s curious because historically, sex work and the arts have had an intimate relationship.

What I found also such a shame about this whole process is that by displacing the communities that live in a place, you really break the link between those communities and their sites of work, you disrupt their legacy by pushing them completely out of the center, out of touch with their history. This prevents the ongoing transmission of the place-based histories of these communities of practice. The conversations with SWAC made this very clear. It’s really hard to cultivate the collective memory of a place, of a community’s culture, when the connections are so fractured on so many levels by gentrification.

Another interesting thing about the brief produced by Stella is that they had compiled a list of negative impacts already observed in the area since its rezoning, even before the 2-22 project was presented to the public. During the period when the gentrification process was in its early stages, as the Quartier des spectacles was first being constructed, they did a field study which showed that not only were sex workers (SWers) already being displaced to other areas, but at the time there were increasing police inspections, constant police presence in the area, and an increasing number of fines being given to “undesirables”. This resulted, as with the demolition of Studio XXX, in job loss, the loss of SWers networks, and an erasure of their collective memory in the neighbourhood. This was a very live issue even before the 2-22 came along.

AG: In the new project, did you find rationale for the need to revitalize the area?

AM: On their website, the SDA uses a number of catchphrases and images to introduce their projects, and one term that comes up a lot is “revitalize,” in this case to “revitalize through culture”.4 It really gives expression to the phenomenon that I have been investigating while working on this project. What it says is that the neighbourhood was “dead” and they needed to revive it by replacing the local culture with a different, more controlled and profitable one.

MD: They saw it as dead, but it certainly wasn’t. There was activity, but they didn’t acknowledge it.

AM: Yes exactly. Often they were invisibilized or illicit activities, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t exist. Actually, in an interview, Gérald Tremblay, the mayor of the City of Montreal at the time of the construction of the 2-22, said that he was sick of seeing boarded up buildings. There’s this desire to make the area profitable at all costs, but not to provide access to housing, to health clinics or things that could really serve the population. You can’t just make art spaces, offices, entertainment and consumer spaces; to allow people to really inhabit a place, to live well, you have to diversify its activities.

AG-MD: As part of your process, you conducted an interview with several SWers, including activists with SWAC. What emerged from this about the relationship between gentrification and sex work?

AM: I think that question is best answered by the collective itself. So I’ll share some of the highlights.

What stood out to me the most in the conversation was that gentrification as a phenomenon is not just about space. It starts with the displacement of communities, yes, but the effects go beyond that. Particularly for SWers, there are the psychological and relational impacts, since displacement affects their ability to offer mutual support.

What’s so impressive is that despite this, SWers find ways to rebuild their connections, to develop new ways to support each other, to be there for each other, and to share the resources they need to do their work. I think that’s really what SWAC is all about.

Something else that often came up in the conversation, is that the more that spaces dedicated to sex work are destroyed, the more isolated SWers find themselves, everybody working alone. This makes solidarity and collective struggle more difficult, but can’t stop it completely; efforts always persist!

These displacements also underline the importance of common spaces, connected to shared professional activities. We can see that it’s in these spaces where exchange and sharing is possible that bonds can develop that transform the spaces into sanctuaries.

A critical issue is that so long as sex work remains a criminalized activity, there is a limit to the safety that sex workers can find in their places of work. They make their own safety, showing incredible resilience despite the ever-increasing urban transformation that hinders their search for security.

What also came up during the exchange is that in Quartier des spectacles, there is a vicious and ironic process of relocating working communities and then taking advantage of their language, their symbols, their tools of representations, to promote the sanitized new district and increase its value. For example, the glass façade of the 2-22 building is apparently a reference to the dancers who stripped in the windows of the Red Light District. The symbolics of these communities are being exploited, while they are denied access to their work, are capitalized upon via the criminalization of their work or simply by their legal exclusion, as we saw with the 2-22.

In addition, by gentrifying and displacing communities and shutting down their places of work, we also reduce their access to services they need. For example, Stella was forced to relocate because of gentrification, which has had a negative impact on SWers’ ability to access the essential, front-line services Stella provides.

I’ll finish by saying that overall, gentrification invisibilizes all these marginalized practices by pushing them further and further from the centre towards more isolated areas, removed from the sight of the rest of society. This puts people in danger, because the more invisible they are, the more at risk they are for violence and abuse. It is a profoundly disturbing impact of gentrification. It’s violence sanctioned by the authorities.

AG-MD: Are you the only artist who has been interested in the building that predates the 2-22?

AM: I did find other artists who were interested in it and wanted to document the existence of the peep show, before it was demolished.

One is Mia Donovan, a photographer and documentary filmmaker who spent her early career documenting the sex work milieu. During that time, she made a series of photographs with SWers at the former Studio XXX.5 As far as I know, these are some of the only images we have of the interior of the space before its demolition.

Another is Angela Grauerholz, also a visual artist, who shot a video of the intersection in 2005. At that time, we could see an overhead projection of two dancers in the window of Studio XXX, on the corner of Saint-Laurent and Sainte-Catherine.

These artists have documented the existence of these SWers by foregrounding them in their places of work. They were really interested in the physicality, the incarnate presence of the bodies of the SWers in those spaces, and not just the building itself. That made a big impression on me. It’s my hope to delve into the connections, of which there are many, between sex work and the arts. Many sex workers make art and many artists do sex work. I think we have a lot to learn and share.

dans le souffle de c. was presented at VOX Contemporary Image Center, from September 9th to December 3rd 2022 as part of the exhibition The Radical Imaginary II: Reclaiming Value.

You can find other documentary resources that informed the project on its web counterpart: https://tinyurl.com/danslesoufledec

1. To learn more about the fight for Café Cléopâtre: Wikipedia. (s.d). Café Cléopâtre, from https://tinyurl.com/cafecleopatre ↩

2. Stella is a community-based organization that seeks to improve quality of life for sex workers, to raise awareness and to educate society at large about the realities and forms of sex work so that sex workers have equal rights to health and safety as the rest of the population. For more information see: https://chezstella.org/ ↩

3. To read the brief produced by Stella: Stella. (2009). Mémoire sur la requalification du Quartier des spectacles, from https://tinyurl.com/quartierdesspectacles ↩

4. Société de développement Angus. (n.d.). Le 2-22, from https://tinyurl.com/le2-22saintlaurent ↩

5. This photo series was presented at Monument National in 2008 as part of the exhibition Le Coin produced by UMA, la Maison de l’image et de la photographie. The three selected artists were invited to document the intersection of St-Laurent and St-Catherine streets, on the cusp of its transformation. To learn more about this exhibition: UMA, la Maison de l’image et de la photographie. (2008). Le Coin, from http://www.umamontreal.com/lecoin/ ↩