Every Mother is a Working Mother

Par Adore Goldman et Latsami, translated by Fred Burrill

In our society, sexuality is a commodity all women are forced to “sell” in one way or another. Our poverty as women leaves us little choice. Hookers get hard cash for their sexual services while other women get a roof over their heads or a night out.1

This text is a summary of a workers’ investigation that we carried out. We interviewed three mothers/parents who are also sex workers in order to explore their experience of motherhood/parenthood, focusing particularly on their antagonistic relationship with the institutions of the State.

- Rebecca is a white woman, mother of two young children of whom she has partial custody. She started sex work after having separated from the father of her children. Over the years, she has worked as a camgirl and an escort.

- Anita is a queer Indigenous person and the parent of two children who are now an adult and a teenager. They have been a sex worker since the late 1990s and have worked in several parts of the industry. They are now a community organizer and an escort. They are also a former drug user, which brought them into contact with different health and social service institutions.

- Chantal is an Indigenous single mother to a 16-year old girl. She has worked in the sex industry since the age of 14 and is currently an erotic masseuse.

For all of them, sex work has been a tool in the struggle against the economic precarity too often experienced by single mothers. The use of this strategy is nevertheless judged extremely harshly, and the stigma that comes with it impacts their children. Too often, stigmatization is a precursor to repression. The threat of a call to youth protection is used to control sex workers, whether it be by ex-partners, landlords, or different actors in health and social services.

The Madonna and the Whore

We operate from the understanding that sex and motherhood are both part of the category of domestic labour, and that this labour is employed to reproduce the workforce – both today’s and tomorrow’s. In giving birth to, caring for, and educating children, women and queer/trans people are producing the next generation of workers. Within the context of the heterosexual couple, it is most often women who cook, clean, and make themselves sexually available in order to ensure that today’s workers are fresh and ready to return to the job. Sexual labour, much like maternity, is a duty that women must carry out with love, but most importantly without pay. Thus is born the two categories of women: the respectable and honest woman on the one hand, and on the other, the perverted, the deviant, who refuses to carry out this work for free, especially when it comes to sex. This dichotomy confines women to domestic labour while depriving them of wages and of power over their working conditions. In this context, the criminalization of sex workers is an essential part of the application of these policies.

Colonization also played an important role in the categorization of certain sexualities as deviant. According to Cree-Métis professor and researcher Kim Anderson, Indigenous women are seen through the lens of the Virgin-Whore complex, translated in the colonial imaginary as the “S*5-Princess.”6 On the one hand, the princess image invokes the “virgin frontier, pure border waiting to be crossed”7, most popularly associated with the character of Pocahontas. Over time, as Indigenous women refused the “princess” label, the colonial power structure instead imposed that of the “s*”, a lazy, obscene, and immoral woman. In both cases, however, the imposed image was a sexualized one that increased patriarchal, colonial domination. Anderson points out that the invention of this stereotypical figure legitimized the removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities and their placement in residential schools and foster homes. These images, she argues, «are like a disease that has spread through both the Native and the non-native mindset»8 and have no connection to any lived reality.

It is therefore to the great advantage of the capitalist, patriarchal, and colonial State to control women’s sexuality and to divide them into “good” and “bad.” Through this process, it ensures the reproduction of its workforce and its colonial domination.

Precarious and in Solidarity!

Working mothers, they stick together! – Anita

When Rebecca started doing sex work, it was to provide a better quality of life for her children after her separation. Without a diploma, she could see clearly that the jobs available to her would not allow her to make ends meet. “I did my budget and I could see that it wasn’t going to work!” she says. A friend introduced her to the sex industry, first as a camgirl and then as an escort. This work enabled her to make more money in less time, and to have a more flexible schedule. “I had time to take my daughter to gymnastics at 4PM and spend time with my kids!” The same was true for Chantal. When she was on social assistance, sex work helped her find money to take care of herself and her daughter. “I tried to find a ‘normal’ job, but after a 40-hour week, you come out with $400. I could make $700 in 12 hours at the [massage] parlour.”

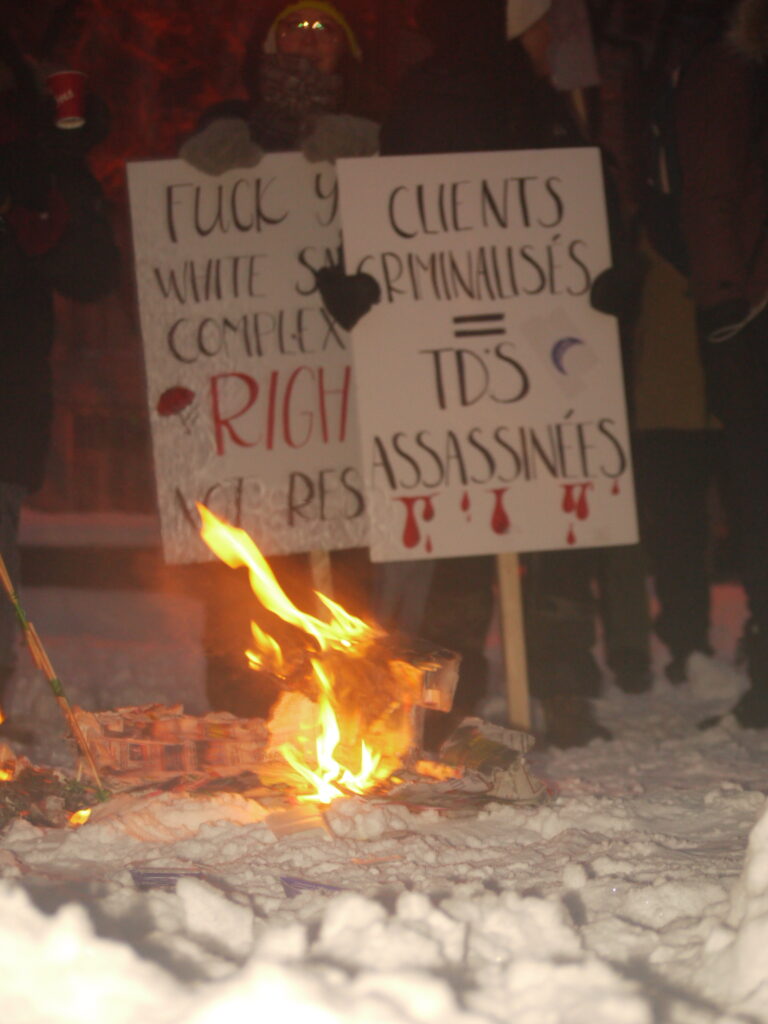

All the same, sex work remains precarious labour. For Anita and Chantal, both of whom worked in massage parlours, 12-hour shifts were a problem. Chantal had to find a place for her daughter to stay when she was receiving clients at home. And there is no guarantee that you will make money! And of course, criminalization makes it so that there are no legal protections at work. Faced with these obstacles, sex workers built their own networks of support: “We made arrangements; you take my daughter for my shift and I’ll take your daughter for your shift,” explained Anita. Mutual aid between whores fills the gaps when it comes to atypical childcare needs.

The lived experiences of Anita, Chantal and Rebecca are not exceptions. Women-headed single-parent families are statistically at greater risk of having insufficient incomes.9 This can be explained, amongst other factors, by the fact that a good part of women’s time is taken up in looking after those in their care: in other words, with unpaid labour. In this context, many turn to sex work. The experiences of our interviewees are reflected in the English Collective of Prostitutes’ report, What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Job Like This?10 The Collective compared sex workers’ job conditions with those of other women and a non-binary person who all worked in largely feminized service and care work jobs. One participant, an unemployed single mother, calculated the hours she dedicated to looking after her children. The unpaid hours dedicated to this task surpassed by far the paid hours worked by the others. Also, women with children are often discriminated against in hiring exactly for this reason. Childcare fees represented half of the expenses of these women. In fact, the sex workers interviewed made the most per hour of all the participants. For the Collective, the question that should be posed in light of this report is not why women engage in sex work, but in fact why more women do not.

Son of a Whore or a Grateful Son?11

Sex work also shapes the experience of children and their relationship with their mothers. Anita and Chantal both have children who are old enough to understand what they do for work. For both parents, sex work opened the door for discussions about sexuality, consent, and sexual and reproductive health. These things are part of their job, and they share their expertise with their teenagers. They also share knowledge about community resources, helping their teens to access condoms, STI testing and other forms of contraception.

Chantal hopes that this open approach will ensure that her daughter won’t go through the same things she did: “My mother didn’t talk to me about sexuality. […] When I started [doing sex work], I was young, I was with a pimp, it was very violent. I wonder if the fact that I’m open with my daughter will help her to be more wise. She has access to all kinds of knowledge that I didn’t!” For Anita, it’s important that her children know their rights, whether they’re working in the sex industry or at McDonald’s.

Their children also, however, experience stigma. Being a “son of a whore” is an insult that hits home differently for the kids of sex workers. “My children always wonder if it’s directed at them,” explains Anita. Their kids have heard people talking about sex work from a young age, given their parent’s activism, but Anita explains that it’s only when their daughter got older that she started to understand what it was all about. “It was important to distinguish what was real from what we see in the movies!” It was hard to figure out how to help their kids manage the information. “You don’t want to say it’s a secret, because you don’t want your children to learn to keep secrets, in case they experience abuse. But it can only be shared with people you trust. You can’t tell it to your teacher, for example.” And with good reason, as the consequences for sex workers and their children of being outed are often severe.

Typically feminized professions previously administered by the Church – Catholic and Protestant – were secularized and taken over by the State, and used to repress sex workers. Dr. Nathalie Stake-Doucet, nursing researcher and activist, reports that Florence Nightingale, a pioneer of modern nursing, opined that “sex workers have an inner evil that spontaneously generates disease.”13 In the hygienist understanding of the period, cleanliness was both a physical and moral property. According to Stake-Doucet, Nightingale was also openly in favour of what she thought of as the “civilizing” effect of British colonization of Indigenous territories.

In parallel, the social work profession developed in response to the social problems associated with growing urbanization. Middle-class women became the enforcers of domestic norms amongst the working classes and immigrant families.14 Jane Addams, one of the founders of social work, belonged to the so-called “hygienist” movement.15 In 1890 she helped to found the Home Economics Movement, a coalition of middle-class women who referred to themselves as the “housewives of the nation.” This movement sought to impose new standards of cleanliness and nutrition on families, especially immigrant ones. Addams was also an important figure in the fight against the “white slave trade,” a particularly widely-spread myth of the period claiming that racialized men were kidnapping white women and forcing them to sell sexual services.16

Given the history of these State institutions, it’s no surprise that sex workers still fear coming into contact with them. And once again for good reason: being denounced to youth protection services is a threat constantly used to control sex workers.

When Rebecca disclosed her profession to her mother, she threatened to call youth protection. Because her mother worked in social services, Rebecca was forced to hide her work from all the health professionals in her life: her psychiatrist, her psychologist, her doctor… keeping her accessing adequate care. In the end, her fears were fortunately unfounded: her psychiatrist and her psychologist reacted well to the news. However, her mother informed the father of Rebecca’s kids about her work, and he called youth protection. The file was quickly closed, but it was a very difficult experience for her.

For Anita, the stigmatization started when they were pregnant and went to a treatment center for their drug use. They explained that “when you do street prostitution, everyone thinks that you had no choice, that you were forced into it and are traumatized.” They defended their rights to the healthcare workers: “I was already a proud whore!” A few years later, a psychosocial crisis led them to seek help from a social worker, who informed Anita that if they “fell back” into sex work, she would have no choice but to call youth protection, to which they responded, “It’s saying things like that makes it so that people can’t tell you what they really need from you. If I were in the industry you can be sure I’d never tell you.”

Chantal also had a similar interaction with a social worker. “I was in crisis because my rent was $1000 and my welfare cheque was for $300,” she shared. But her relationship with her social worker was anything but helpful. “He was a pervert: he was always looking at my breasts. When I told him I did massages on the side for extra money, he called youth protection services.” She suspects he wanted sexual services in exchange for his silence. “Maybe by looking at my breasts, he was sending me a message!”

The shortage of family-sized apartments also places sex workers in a vulnerable position. For Rebecca, access to an adequate apartment was a major difficulty that doing sex work allowed her to overcome. “It’s the biggest expense that comes with having kids!” Chantal also experienced this hardship, as the cost of rent greatly exceeded the amount of her monthly welfare cheque. And landlords who find out about the profession of their tenants exploit the information for their own benefit. Chantal’s landlord threatened to denounce her to the authorities if she didn’t move. “It worked. I couldn’t take the risk, so I moved…”

A Struggle for Time

In the light of these testimonies, we can see that the economic precarity of women and queer/trans people is a central factor in the decision to practice sex work, particularly when there are kids to look after. This state of affairs is often used by anti-prostitution activists to defend “the abolition of the sex industry” – which not even the current level of criminalization of sex workers has managed to bring about.

The policies that govern our industry actually increase stigmatization, causing the repression of “bad” mothers who are engaged in sex work. A constantly recurring theme in the testimonies of Rebecca, Anita, and Chantal is that the threat of youth protection causes a lot of fear, but is not accompanied by many resources. After the social worker denounced Chantal, Youth Protection Services didn’t find cause to intervene, but nobody helped her to find an apartment that she could afford.

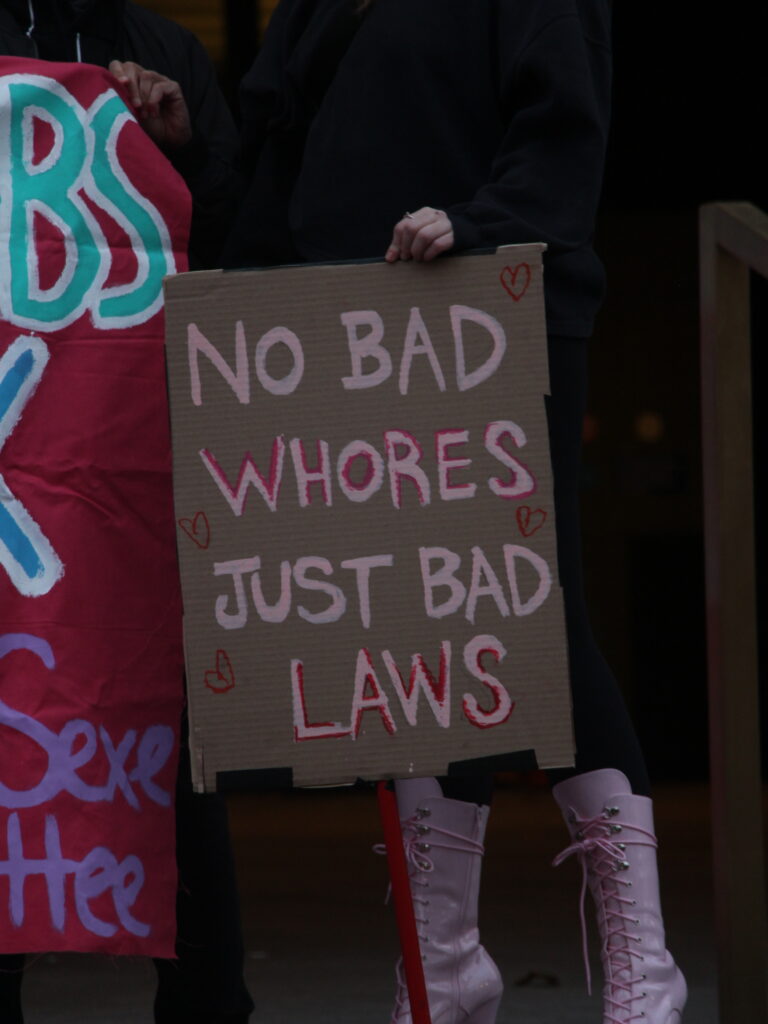

If engaging in sex work is never a choice free from economic constraints, this is true for all the decisions we make in a capitalist world. As sex workers and activists with the Sex Workers Advocacy and Resistance Movement, Juno Mac and Molly Smith argue that “sex workers ask to be credited with the capacity to struggle with work—even hate it—and still be considered workers. You don’t have to like your job to want to keep it.”17

As mothers and as sex workers, claiming our status as workers enables us to demand the resources we need in order to live decently. We’ve named several here: access to an appropriately-sized apartment that we can afford, free childcare adapted to atypical schedules, liveable welfare payments – and why not a salary!

In the end, what comes out of these interviews with Anita, Chantal and Rebecca, is that these sex-worker mothers and parents need less work and more money. As Anita pointed out: “Like other parents, we’re all doing our damnedest to survive and provide for our kids. We want to have more quality time with our kids!”

1. Wages for Housework. (1977). «Housewives & Hookers Come Together», Wages for Housework Campaign Bulletin, vol. 1, no 4, Traduit de l’anglais par Sylvie Dupont dans dans Luttes XXX, Inspirations du mouvement des travailleuses du sexe, 2011, Éditions du remue-ménage. ↩

2.The adoption of the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act made sex work illegal for the first time in Canada. This law forbids the promotion of another person’s sexual services, communication in certain public spaces in order to offer one’s services, materially profiting from sex work, and seeking out sexual services, regardless of the context. ↩

3. Light industry refers to the production of consumer goods such as food or textiles. Heavy industry refers, for example, to mining, steelwork, and railway construction. It requires intensive use of machinery and capital. ↩

4. Silvia Federici. (2021). «Origins and Development of Sexual Work in the United States and Britain», Patriarchy of the Wage. Notes on Marx, Gender, and Feminism, p. 109. ↩

5. As settlers, we have chosen not to employ the S-word as used by Anderson because of its pejorative, racist, and sexist connotations. ↩

6. Kim Anderson. (2000). «Chapter Six. The Construction of a Negative Identity», A Recognition of Being : Reconstructing Native Womanhood, p. 99- 112 ↩

7. Idem, p. 101 ↩

8. Idem, p. 100 ↩

9. In 2019 in Quebec, 30% of single-parent households lived under the poverty line, compared to 9% of dual-parent households. 75% of single-parent households are headed by women. Despite higher employment rates, these families are poorer than single-parent households headed by men.

Conseil du statut de la femme. (2019). Quelques constats sur la monoparentalité au Québec. p.17

Secrétariat à la Condition féminine Québec. (s.d.) Les femmes monoparentales. Quelques données statistiques pour l’égalité entre les hommes et les femmes↩

10. English Collective of Prostitutes. (2019). What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Job Like This? ↩

11. Referring to the Stromae song, Fils de joie (2022). ↩

12. Frédéric Regard. (2014). Féminisme et prostitution dans l’Angleterre du XIXe: la croisade de Josephine Butler. ENS Édition ↩

13. Nathalie Stake-Doucet. (2020). The Racist Lady with the Lamp. Nursing Clio. ↩

14. Mariarosa Dalla Costa. (1997). «Mass production and the new urban order», in Family, Welfare, and the State Between Progressivism and the New Deal, Commons Notion, p.9 ↩

15. Idem, p. 99 ↩

16. Nicole F. Bromfield. (2015). Sex Slavery and Sex Trafficking of Women in the United States, Sage Journals

For more on the white slave trade and the racist history of sex work laws see Jesse Dekel. (2022). A Very Brief Overview of American Anti-Sex Trafficking Laws’ Racist History, SWAC Attacks, 2nd issue ↩

17. Juno Mac, Molly Smith. (2018). Sex Is Not the Problem with Sex Work, Boston Review ↩