Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers' Rights – A review: A manifesto for angry hookers

by Cherry Blue

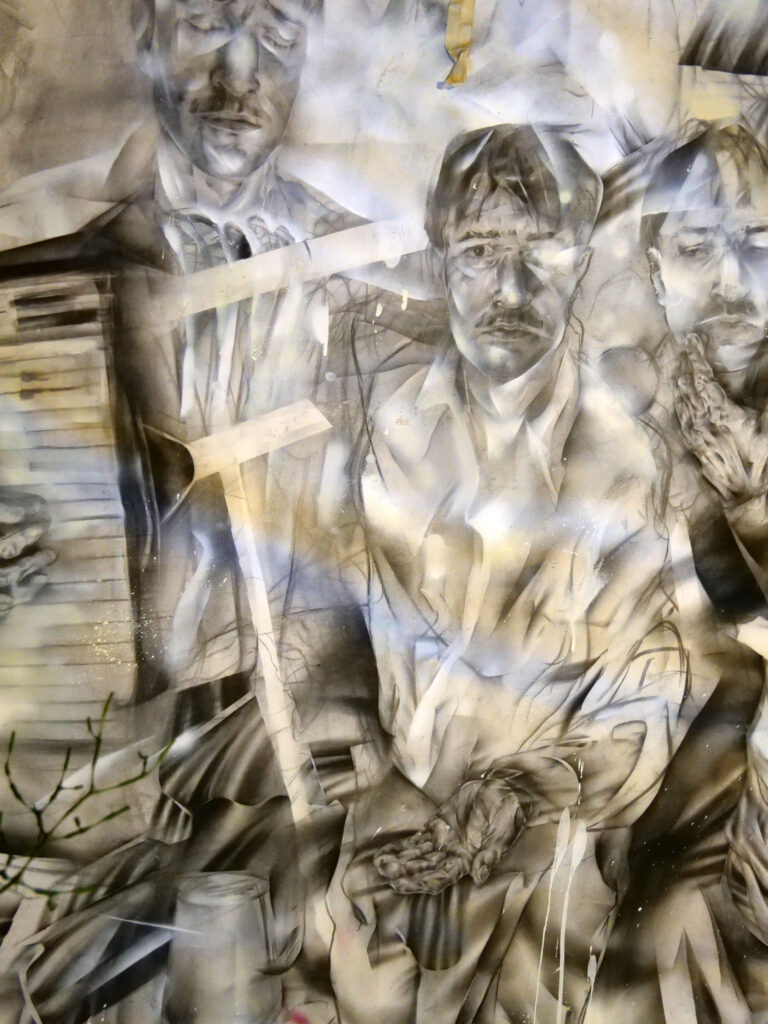

Photo: It was a good day, Céleste Dérosiers, photo by Tanata

Symbolism vs. reality

In the first instance, they make a distinction between the professional dimensions of sex work and their stereotypical representation. They argue that most abolitionists – anti-prostitution activists – seek to build an argument based on metaphorical associations with sexuality and its monetization, without considering the importance of working conditions for the practice. Such moralizing positions take many forms, but the myths undergirding the imagined “prostitute” often prove to be dangerous and disconnected from reality. The prostitute is usually represented as dirty and corrupt, which gradually denies her of her inner worth (p. 11). This odious stereotyping can easily be attributed to a political agenda that seeks to be rid of those exchanging sexual services for money or shelter, notably through “rescue industry” discourse, according to which every SWer is a victim to be saved and therefore in the same bracket as orphaned children and abandoned animals (p. 9).

In response to these preconceptions, many SWers portray their work in terms of “sex positivity” and empowerment. Those who emphasize the role of pleasure in their work, though, are in fact articulating a defensive response to stigma, while only the most privileged can afford to choose their clients and find enjoyment in the work (p. 13). This position ends up harming SWer communities by not representing the experience of the less privileged, casting a veil over precariousness and the demands of those who wish to obtain better working conditions. Further to this, these assumptions create the illusion that customers and workers share the same interests (p. 32). But the person selling sex needs the transaction more than the customer, which makes workers more vulnerable. In the end, SWers unhappy with their current conditions end up feeling stuck between the “happy hooker” who enjoy certain privileges, and the abolitionists who seek to deny their rights (p. 36).

The dangers of carceral feminism

Both pro-decriminalization and anti-prostitution feminists often articulate their positions by drawing on legacies of violence. Anti-prostitution feminists assert that the best possibility of justice against male violence is found in carceral feminism. This school of thought supports putting forward a set of punitive laws, because “exited women come to be regarded as the ultimate symbol of female woundedness, with the criminalisation of clients as feminist justice” (p.13). However, this ignores the police violence – material and historical – against women and racialized people. This is particularly true for migrant SWers, who are criminalized and at risk of deportation if they need to report sexual abuse. “For sex workers and other marginalised and criminalised groups, the police are not a symbol of protection but a real manifestation of punishment and control” (p. 16): laws are not just symbolic, they have a demonstrable impact on police power – its violence and use of profiling.

Some might argue that the Nordic model – criminalizing the purchase of sexual services – only targets clients and not SWers. In which case, this model would not harm the latter group. But any approach that aims to reduce money changing hands in the sex industry makes those who offer sexual services take on the consequences of lower demand – and this is true both in terms of their working conditions and their income (p. 54).

Pushing back on lazy assumptions: whoring is working

The arguments that abolitionists make often involve obfuscating the professional aspect of this practice: “Don’t say sex work, it’s far too awful to be work” (p. 42). Labor and awfulness are positioned as antithetical; if sex work is strenuous, it can’t be work. This argument forgets that waged labor is generally a form of exploitation; bosses profit from the work of their employees by paying them less than the income that they generate. Thus, it is unreasonable to consider any and all work, including sex work, is morally good by default (pp. 45-46).

Both bad clients and abolitionists seem to think that there are no limits placed by SWers in the sexual act, as if the latter put themselves at the disposal of all the wishes of the client, who is able to do whatever he wants with their bodies. Although it would be shocking to say the same thing about a massage therapist, we don’t mind perpetuating this false account of sex work. The authors quote an escort named Nikita: “Part of believing me when I say I have been raped is believing me when I say I haven’t been” (p. 45). They explain that in today’s society, penetration is always assumed to be an act of domination. If the act of penetration is always already perceived as degrading, sex work will inevitably be framed negatively and misogynistically. We have much to gain from modifying our shared assumptions about penetration, which is not intrinsically a “denigrating” act for the person who is penetrated.

An economic necessity

It can also be dangerous to fail to recognize the economic and material factors that motivate SWers. The idea that, because they are too weird and broken (p. 48), SWers are incapable of making good decisions for themselves not only robs them of their agency, but prioritizes punitive reforms over a feminist utopia. Smith and Mac cite the example of a court in Sweden that took custody of a SWer’s child away from her abusive father, who eventually killed the child’s mother (p. 47).

Although it is true that SWers are more likely to have experienced sexual trauma/abuse at the hands of their family, those that have chose to pursue sex work do so not because of some “permanent damage” that leads to self-destruction, but because of the economic precariousness that is more widespread among victims of such abuse. Other jobs offered to women, especially those without qualifications, are generally underpaid. Women are more likely than men to be unemployed or underpaid. Faced with these obstacles, sometimes the only viable option is sex work: “Anti-prostitution campaigners should take seriously the fact that sex work is a way people get the resources they need” (p. 52). This scenario plays out with higher frequency for racialized women and LGBTQIA+ people, resulting in their overrepresentation in the industry.

The problem of borders

Mobilizing to defend the rights of SWers must involve consideration of the situation for migrants. In 2021 in the United States, the anti-sex trafficking budget amounted to more than 1.2 billion USD – mainly for “information campaigns” and not to help survivors – while in 2013, the budget for SWers rights was 10 million globally (p. 59). Since SWers are considered to be offenders as well as victims, the U.S. government prevents anyone who has sold sexual services in the last ten years from entering the country, in the same bracket as spies, Nazis and terrorists (p. 81). Crossing into the U.S. is always anxiety-inducing for a SWer: border agents can search their phone for evidence without needing any proof or warrant.

In the world of sex trafficking, it is important to distinguish between kidnapping and voluntary migration. The scenario in which a young white girl is kidnapped and abused in another country is ultimately very rare. Most sex trafficking involves people looking to immigrate and pay smuggling networks to do so, often facing sexual exploitation since being undocumented means having few to no rights. We should not place blame on these migrants and instead change the system that prevents them from migrating legally and accessing the same rights as those with citizenship.

Fuelled by stories perpetuated by the media and popular culture, some argue that there is a system enslaving young white girls today that is even more serious than the slavery of African Americans. However, this falsehood is very dangerous and distracts us from the fact that “the direct modern descendant of chattel slavery in the US is not prostitution but the prison system” (p. 76). Indeed, there are more African Americans incarcerated in the United States than there were slaves in 1850. Moreover, the appropriation of the term “abolitionist” by so-called anti-prostitution feminists, in reference to the fight to abolish slavery, is an attempt to gain moral legitimacy via the suggestion that the two struggles are equivalent. However, anti-prostitution groups are generally made up of white conservatives, whereas those impacted by criminalization are often African Americans (p. 78).

Ultimately, the root of the problem is that borders “make people vulnerable, and that vulnerability is what abusive people prey upon” (p. 64). In other words, the criminalization of undocumented migrants directly creates the market for sex trafficking. The nation-state finds a scapegoat (in this case the trafficker) to distract people from the actual problem: borders and the prison system. So it is important to keep in mind that the distinction between sex trafficking and sex work should not encourage the belief that the arrests of trafficking victims are any more justifiable; we must be critical of borders and the role they play in migrants’ precarity. This forms the essential disagreement between carceral feminists and pro-rights feminists: “We disagree not only on the solution, but on the problem: for carceral feminists, the problem is commercial sex, which produces trafficking; for us, the problem is borders” (p. 83).

The distinction that is often made between sex work and sex trafficking provides ready evidence that our solidarity is too often granted solely to SWers with citizenship. It is all too easy to avoid the question of sex trafficking: this blindspot allows us to ignore the gray areas that threaten to delegitimize us in the eyes of society at large. However, there needs to be space for migrant SWers within our struggle if we want to improve rights for all: “There is no migrant solidarity without prostitute solidarity and there is no prostitute solidarity without migrant solidarity” (p. 86).

The authors believe that politicizing a SWer takes about two minutes. They live or come into close contact with situations of injustice and oppression, which motivates them to get involved in political organizing. Unfortunately, only a handful of activists can afford to be public with their demands and are granted more of the credit for their actions. We should always be alert to the voices of all SWers, regardless of their backgrounds or modes of communication. Disgruntled whores, precarious whores, migrant whores; you are not alone.

1. Juno Mac et Molly Smith. (2018). Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Right, Verso.↩