Privacy online: a myth?

Privacy online : a myth?

A few tips to ensure your security

By celeste and susie showers

- Encrypted software like Signal and Protonmail are only secure end-to-end when both the receiver and the sender are using the same service. Example when you send a message from your PM account to a Gmail address, the data is still exposed.

- Use complicated safe passwords with uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers and symbols.4

- Set up the two-step authentication in your online accounts when possible.

- Sign out of social media accounts before leaving the page, as when you’re signed in your browsing behaviour is tracked on any other pages you open.

- Use a VPN like TunnelBear to hide your location.

- Use incognito mode when using your browser.5

- Use an extension on your browsers to block ads.

- Manually disable data collection on the websites you use if possible.

Secure your content

- Make images of yourself less recognizable (For example, close-up angles that do not show recognizable parts of the body, such as the face, tattoos, etc.)

- Before posting SW related images, remove EXIF data, which is a time and location stamp embedded in the photo. Use iphone app Shortcuts to automize or search how to delete EXIF data on your specific cell phone model.

- Don’t post your location on Instagram stories or Snapchat while you are there, wait until you are at another location.

- On your website, pay for the extra privacy that does not reveal the domain purchaser’s name and address.6

- Keep your legal name off PayPal transactions by creating a business account and using DBA (Doing Business As) as the name. Alternatively, If you link your account to your debit card rather than a credit card, it doesn’t show any name. Check by sending a small transfer of $0.01 to a trusted person and ask them what information is shown on their statement.

- Depending on your bank, it is also possible to change the name on your statement. You can put your initials for example.

Secure your ways of communicating

No apps and platforms are totally secure, and many sites are dropping SWers as rules and guidelines change quickly and without warning.

- Use code words on forums when talking about services.

- Do not talk about money or explicit services directly.

- Check community guidelines before posting on SWers forums.

- An email list is the most secure way to keep in touch with clients.

- When crossing borders, bring as little electronic devices as possible.

- Set all social media accounts to private.

- Delete ALL images and messages on your devices that might be related to SW in any way.

- Add a numerical password on your smartphone.7

- Change notification settings to not show any message content on the lock screen.

- Advertise your dates outside of the dates you are travelling.

- Take down any ads with your image on it before you travel.

This advice is subject to change quickly because of the ever evolving online world. Our best weapon against political online attacks are solidarity and organisation among colleagues to obtain changes.

1.The Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) and Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) were passed by the U.S. Senate in 2018. Since then, platforms that knowingly host content that facilitates prostitution have been held accountable. These laws, which are supposed to address sex trafficking, cast a wider net: they come to criminalize any site hosting content associated with prostitution. So it’s no surprise that several social media sites, like Tumblr and Instagram, have decided to change their standards to no longer accept SW content on their platforms.

↩

2. Thorin Klosowski. (s.-d.). How to Protect Your Digital Privacy ↩

3. To know more on the closure of Backpage and other consequences of SESTA-FOSTA: Adore Goldman, Celeste. (2021). Crusade Against Porn, SWAC Attacks↩

4. Thorin Klosowski. (s.-d.). How to Protect Your Digital Privacy. ↩

5. Dan Raywood. (2018). Top Ten Ways to Reduce Your Digital Footprint. ↩

6. Hacking hustling. (2019). Online Worker Safety Hazards and Cautions : A Practical Harm Reduction Guide on Why and How Sex Workers Can Protect Ourselves at Work ↩

Every Mother is a Working Mother

Every Mother is a Working Mother

Par Adore Goldman et Latsami, translated by Fred Burrill

In our society, sexuality is a commodity all women are forced to “sell” in one way or another. Our poverty as women leaves us little choice. Hookers get hard cash for their sexual services while other women get a roof over their heads or a night out.1

This text is a summary of a workers’ investigation that we carried out. We interviewed three mothers/parents who are also sex workers in order to explore their experience of motherhood/parenthood, focusing particularly on their antagonistic relationship with the institutions of the State.

- Rebecca is a white woman, mother of two young children of whom she has partial custody. She started sex work after having separated from the father of her children. Over the years, she has worked as a camgirl and an escort.

- Anita is a queer Indigenous person and the parent of two children who are now an adult and a teenager. They have been a sex worker since the late 1990s and have worked in several parts of the industry. They are now a community organizer and an escort. They are also a former drug user, which brought them into contact with different health and social service institutions.

- Chantal is an Indigenous single mother to a 16-year old girl. She has worked in the sex industry since the age of 14 and is currently an erotic masseuse.

For all of them, sex work has been a tool in the struggle against the economic precarity too often experienced by single mothers. The use of this strategy is nevertheless judged extremely harshly, and the stigma that comes with it impacts their children. Too often, stigmatization is a precursor to repression. The threat of a call to youth protection is used to control sex workers, whether it be by ex-partners, landlords, or different actors in health and social services.

The Madonna and the Whore

We operate from the understanding that sex and motherhood are both part of the category of domestic labour, and that this labour is employed to reproduce the workforce – both today’s and tomorrow’s. In giving birth to, caring for, and educating children, women and queer/trans people are producing the next generation of workers. Within the context of the heterosexual couple, it is most often women who cook, clean, and make themselves sexually available in order to ensure that today’s workers are fresh and ready to return to the job. Sexual labour, much like maternity, is a duty that women must carry out with love, but most importantly without pay. Thus is born the two categories of women: the respectable and honest woman on the one hand, and on the other, the perverted, the deviant, who refuses to carry out this work for free, especially when it comes to sex. This dichotomy confines women to domestic labour while depriving them of wages and of power over their working conditions. In this context, the criminalization of sex workers is an essential part of the application of these policies.

Colonization also played an important role in the categorization of certain sexualities as deviant. According to Cree-Métis professor and researcher Kim Anderson, Indigenous women are seen through the lens of the Virgin-Whore complex, translated in the colonial imaginary as the “S*5-Princess.”6 On the one hand, the princess image invokes the “virgin frontier, pure border waiting to be crossed”7, most popularly associated with the character of Pocahontas. Over time, as Indigenous women refused the “princess” label, the colonial power structure instead imposed that of the “s*”, a lazy, obscene, and immoral woman. In both cases, however, the imposed image was a sexualized one that increased patriarchal, colonial domination. Anderson points out that the invention of this stereotypical figure legitimized the removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities and their placement in residential schools and foster homes. These images, she argues, «are like a disease that has spread through both the Native and the non-native mindset»8 and have no connection to any lived reality.

It is therefore to the great advantage of the capitalist, patriarchal, and colonial State to control women’s sexuality and to divide them into “good” and “bad.” Through this process, it ensures the reproduction of its workforce and its colonial domination.

Precarious and in Solidarity!

Working mothers, they stick together! – Anita

When Rebecca started doing sex work, it was to provide a better quality of life for her children after her separation. Without a diploma, she could see clearly that the jobs available to her would not allow her to make ends meet. “I did my budget and I could see that it wasn’t going to work!” she says. A friend introduced her to the sex industry, first as a camgirl and then as an escort. This work enabled her to make more money in less time, and to have a more flexible schedule. “I had time to take my daughter to gymnastics at 4PM and spend time with my kids!” The same was true for Chantal. When she was on social assistance, sex work helped her find money to take care of herself and her daughter. “I tried to find a ‘normal’ job, but after a 40-hour week, you come out with $400. I could make $700 in 12 hours at the [massage] parlour.”

All the same, sex work remains precarious labour. For Anita and Chantal, both of whom worked in massage parlours, 12-hour shifts were a problem. Chantal had to find a place for her daughter to stay when she was receiving clients at home. And there is no guarantee that you will make money! And of course, criminalization makes it so that there are no legal protections at work. Faced with these obstacles, sex workers built their own networks of support: “We made arrangements; you take my daughter for my shift and I’ll take your daughter for your shift,” explained Anita. Mutual aid between whores fills the gaps when it comes to atypical childcare needs.

The lived experiences of Anita, Chantal and Rebecca are not exceptions. Women-headed single-parent families are statistically at greater risk of having insufficient incomes.9 This can be explained, amongst other factors, by the fact that a good part of women’s time is taken up in looking after those in their care: in other words, with unpaid labour. In this context, many turn to sex work. The experiences of our interviewees are reflected in the English Collective of Prostitutes’ report, What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Job Like This?10 The Collective compared sex workers’ job conditions with those of other women and a non-binary person who all worked in largely feminized service and care work jobs. One participant, an unemployed single mother, calculated the hours she dedicated to looking after her children. The unpaid hours dedicated to this task surpassed by far the paid hours worked by the others. Also, women with children are often discriminated against in hiring exactly for this reason. Childcare fees represented half of the expenses of these women. In fact, the sex workers interviewed made the most per hour of all the participants. For the Collective, the question that should be posed in light of this report is not why women engage in sex work, but in fact why more women do not.

Son of a Whore or a Grateful Son?11

Sex work also shapes the experience of children and their relationship with their mothers. Anita and Chantal both have children who are old enough to understand what they do for work. For both parents, sex work opened the door for discussions about sexuality, consent, and sexual and reproductive health. These things are part of their job, and they share their expertise with their teenagers. They also share knowledge about community resources, helping their teens to access condoms, STI testing and other forms of contraception.

Chantal hopes that this open approach will ensure that her daughter won’t go through the same things she did: “My mother didn’t talk to me about sexuality. […] When I started [doing sex work], I was young, I was with a pimp, it was very violent. I wonder if the fact that I’m open with my daughter will help her to be more wise. She has access to all kinds of knowledge that I didn’t!” For Anita, it’s important that her children know their rights, whether they’re working in the sex industry or at McDonald’s.

Their children also, however, experience stigma. Being a “son of a whore” is an insult that hits home differently for the kids of sex workers. “My children always wonder if it’s directed at them,” explains Anita. Their kids have heard people talking about sex work from a young age, given their parent’s activism, but Anita explains that it’s only when their daughter got older that she started to understand what it was all about. “It was important to distinguish what was real from what we see in the movies!” It was hard to figure out how to help their kids manage the information. “You don’t want to say it’s a secret, because you don’t want your children to learn to keep secrets, in case they experience abuse. But it can only be shared with people you trust. You can’t tell it to your teacher, for example.” And with good reason, as the consequences for sex workers and their children of being outed are often severe.

Typically feminized professions previously administered by the Church – Catholic and Protestant – were secularized and taken over by the State, and used to repress sex workers. Dr. Nathalie Stake-Doucet, nursing researcher and activist, reports that Florence Nightingale, a pioneer of modern nursing, opined that “sex workers have an inner evil that spontaneously generates disease.”13 In the hygienist understanding of the period, cleanliness was both a physical and moral property. According to Stake-Doucet, Nightingale was also openly in favour of what she thought of as the “civilizing” effect of British colonization of Indigenous territories.

In parallel, the social work profession developed in response to the social problems associated with growing urbanization. Middle-class women became the enforcers of domestic norms amongst the working classes and immigrant families.14 Jane Addams, one of the founders of social work, belonged to the so-called “hygienist” movement.15 In 1890 she helped to found the Home Economics Movement, a coalition of middle-class women who referred to themselves as the “housewives of the nation.” This movement sought to impose new standards of cleanliness and nutrition on families, especially immigrant ones. Addams was also an important figure in the fight against the “white slave trade,” a particularly widely-spread myth of the period claiming that racialized men were kidnapping white women and forcing them to sell sexual services.16

Given the history of these State institutions, it’s no surprise that sex workers still fear coming into contact with them. And once again for good reason: being denounced to youth protection services is a threat constantly used to control sex workers.

When Rebecca disclosed her profession to her mother, she threatened to call youth protection. Because her mother worked in social services, Rebecca was forced to hide her work from all the health professionals in her life: her psychiatrist, her psychologist, her doctor… keeping her accessing adequate care. In the end, her fears were fortunately unfounded: her psychiatrist and her psychologist reacted well to the news. However, her mother informed the father of Rebecca’s kids about her work, and he called youth protection. The file was quickly closed, but it was a very difficult experience for her.

For Anita, the stigmatization started when they were pregnant and went to a treatment center for their drug use. They explained that “when you do street prostitution, everyone thinks that you had no choice, that you were forced into it and are traumatized.” They defended their rights to the healthcare workers: “I was already a proud whore!” A few years later, a psychosocial crisis led them to seek help from a social worker, who informed Anita that if they “fell back” into sex work, she would have no choice but to call youth protection, to which they responded, “It’s saying things like that makes it so that people can’t tell you what they really need from you. If I were in the industry you can be sure I’d never tell you.”

Chantal also had a similar interaction with a social worker. “I was in crisis because my rent was $1000 and my welfare cheque was for $300,” she shared. But her relationship with her social worker was anything but helpful. “He was a pervert: he was always looking at my breasts. When I told him I did massages on the side for extra money, he called youth protection services.” She suspects he wanted sexual services in exchange for his silence. “Maybe by looking at my breasts, he was sending me a message!”

The shortage of family-sized apartments also places sex workers in a vulnerable position. For Rebecca, access to an adequate apartment was a major difficulty that doing sex work allowed her to overcome. “It’s the biggest expense that comes with having kids!” Chantal also experienced this hardship, as the cost of rent greatly exceeded the amount of her monthly welfare cheque. And landlords who find out about the profession of their tenants exploit the information for their own benefit. Chantal’s landlord threatened to denounce her to the authorities if she didn’t move. “It worked. I couldn’t take the risk, so I moved…”

A Struggle for Time

In the light of these testimonies, we can see that the economic precarity of women and queer/trans people is a central factor in the decision to practice sex work, particularly when there are kids to look after. This state of affairs is often used by anti-prostitution activists to defend “the abolition of the sex industry” – which not even the current level of criminalization of sex workers has managed to bring about.

The policies that govern our industry actually increase stigmatization, causing the repression of “bad” mothers who are engaged in sex work. A constantly recurring theme in the testimonies of Rebecca, Anita, and Chantal is that the threat of youth protection causes a lot of fear, but is not accompanied by many resources. After the social worker denounced Chantal, Youth Protection Services didn’t find cause to intervene, but nobody helped her to find an apartment that she could afford.

If engaging in sex work is never a choice free from economic constraints, this is true for all the decisions we make in a capitalist world. As sex workers and activists with the Sex Workers Advocacy and Resistance Movement, Juno Mac and Molly Smith argue that “sex workers ask to be credited with the capacity to struggle with work—even hate it—and still be considered workers. You don’t have to like your job to want to keep it.”17

As mothers and as sex workers, claiming our status as workers enables us to demand the resources we need in order to live decently. We’ve named several here: access to an appropriately-sized apartment that we can afford, free childcare adapted to atypical schedules, liveable welfare payments – and why not a salary!

In the end, what comes out of these interviews with Anita, Chantal and Rebecca, is that these sex-worker mothers and parents need less work and more money. As Anita pointed out: “Like other parents, we’re all doing our damnedest to survive and provide for our kids. We want to have more quality time with our kids!”

1. Wages for Housework. (1977). «Housewives & Hookers Come Together», Wages for Housework Campaign Bulletin, vol. 1, no 4, Traduit de l’anglais par Sylvie Dupont dans dans Luttes XXX, Inspirations du mouvement des travailleuses du sexe, 2011, Éditions du remue-ménage. ↩

2.The adoption of the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act made sex work illegal for the first time in Canada. This law forbids the promotion of another person’s sexual services, communication in certain public spaces in order to offer one’s services, materially profiting from sex work, and seeking out sexual services, regardless of the context. ↩

3. Light industry refers to the production of consumer goods such as food or textiles. Heavy industry refers, for example, to mining, steelwork, and railway construction. It requires intensive use of machinery and capital. ↩

4. Silvia Federici. (2021). «Origins and Development of Sexual Work in the United States and Britain», Patriarchy of the Wage. Notes on Marx, Gender, and Feminism, p. 109. ↩

5. As settlers, we have chosen not to employ the S-word as used by Anderson because of its pejorative, racist, and sexist connotations. ↩

6. Kim Anderson. (2000). «Chapter Six. The Construction of a Negative Identity», A Recognition of Being : Reconstructing Native Womanhood, p. 99- 112 ↩

7. Idem, p. 101 ↩

8. Idem, p. 100 ↩

9. In 2019 in Quebec, 30% of single-parent households lived under the poverty line, compared to 9% of dual-parent households. 75% of single-parent households are headed by women. Despite higher employment rates, these families are poorer than single-parent households headed by men.

Conseil du statut de la femme. (2019). Quelques constats sur la monoparentalité au Québec. p.17

Secrétariat à la Condition féminine Québec. (s.d.) Les femmes monoparentales. Quelques données statistiques pour l’égalité entre les hommes et les femmes↩

10. English Collective of Prostitutes. (2019). What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Job Like This? ↩

11. Referring to the Stromae song, Fils de joie (2022). ↩

12. Frédéric Regard. (2014). Féminisme et prostitution dans l’Angleterre du XIXe: la croisade de Josephine Butler. ENS Édition ↩

13. Nathalie Stake-Doucet. (2020). The Racist Lady with the Lamp. Nursing Clio. ↩

14. Mariarosa Dalla Costa. (1997). «Mass production and the new urban order», in Family, Welfare, and the State Between Progressivism and the New Deal, Commons Notion, p.9 ↩

15. Idem, p. 99 ↩

16. Nicole F. Bromfield. (2015). Sex Slavery and Sex Trafficking of Women in the United States, Sage Journals

For more on the white slave trade and the racist history of sex work laws see Jesse Dekel. (2022). A Very Brief Overview of American Anti-Sex Trafficking Laws’ Racist History, SWAC Attacks, 2nd issue ↩

17. Juno Mac, Molly Smith. (2018). Sex Is Not the Problem with Sex Work, Boston Review ↩

Haze of thoughts

Haze of thoughts

Céleste

Choosing to work in this industry brought me first and foremost a job. I could finally work less hours and earn a lot more. In this scene that is shamed and a bit apart from the rest of this reality, some thoughts came to me throughout my experiences. Sometimes it’s teachings I remembered or new perspectives that opened up. So here are thoughts I wrote down during these last few years.

Hope is partly radical openness.

While trying to keep on living in this rotting world, I search for meaning and hope everywhere. Some glimpses are offered to me in the details of life and in my loved ones.

I have come to believe that a feeling of hope can emerge from radical openness to the world and others around us. If we can decenter ourselves from what we are experiencing in the moment, it can bring more connection in between others. The lifelong journey of letting go of our biases can only do good to us and to others. Being open to receive anything the other brings without judgment can ease some of the loneliness we all feel. Hope doesn’t have to be total to be there. It can be seen in the thin light of the possibility of continuing or the chaining to continuity. Openness can show us that nothing is over and everything can still happen.

The best and worst of humanity is intertwined in these spaces.

Like everywhere we look, we can find duality in our human world and imagination. In this industry where clients can fulfill their fantasies and their needs of connection and intimacy, I met the most incredible people. These colleagues were glowing effortlessly. Their passion, curiosity, movements and sensitivity were so strong that I couldn’t look past them. They inspired me to know myself more. They taught me more about empathy and holding space than anywhere else. There is also the worst kind of people in these spaces. Abusers that have no concern for others. People so disconnected that they make no sense to me. Their frivolous concerns for money, appearances, social norms and their ego separates them from others as well as shapes their interpersonal relationships. Men will trust other men for the sole reason that they have had successful financial dealings with each other. They protect their own. They feed their dark emotions so much that it consumes them. it’s easier to stay aligned with these feelings rather than accept another being with their own set views. It was always fascinating and unbearable to me to witness and to be part of a small world governed by money, addictions and heteronormativity in which intimacy and deep connections can bloom anyways.

Protect your heart.

With learning to be there for yourself, comes finding ways to protect your heart. Anything can take the form of bringing you some ease if you wish it to. Maybe the first way that you found to protect your heart was dissociating. Leaving this reality to access some peace far away. To be somewhere else can bring you so much, it can help you survive. I got lost in my hiding spot and I feel that what can help save you is coming back to yourself. Be the closest you can to you. Know what soothes you, what helps you go on.

With love,

Céleste

From Red Light to Quartier des Spectacles

From Red Light to Quartier des spectacles

Cultural and creative industries, sex work, and gentrification

Interview by Maxime Durocher and Adore Goldman, Translated by Hannah Azar Strauss

AM Trépanier is an artist-researcher, editor, and cultural worker. Across their practice, they explore the particularities of different media, technologies, and actions to (re)mediate the discourse around a given situation. Their artistic practices take the form of publications, video, conversation, websites, and exhibitions. In their work, they pay close attention to the tactics used by marginalized communities and alternative publics to build new kinds of spaces, gain access to information, and appropriate various technical tools.

AM collaborated with the Sex Work Autonomous Committee (SWAC) as part of the project dans le souffle de c., which explores the processes of urban gentrification resulting in the re-purposing of a site dedicated to sex work into an imposing hub of artistic and cultural dissemination: the 2-22. We asked them to tell us more about their process and the discoveries of the research.

Adore Goldman (AG) and Maxime Durocher (MD): How did you become interested in the history of the 2-22?

AM Trépanier (AM): In the fall of 2021, I was invited to participate in a group exhibition reflecting from a critical perspective on the notion of value, beyond its definition by the market economy. The curators wanted to create a space that could present various postures taken by artists towards the institution of the economy.

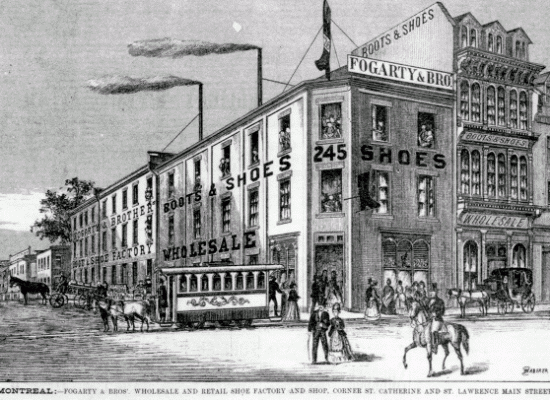

As a starting point for the project, I did some generic research on the history of the place where the exhibition is located: VOX, a center for the research and dissemination of contemporary images, is housed in a cultural complex called the 2-22, located at the corner of Saint-Laurent and Sainte-Catherine. While delving into the history of the 2-22, built by the Société de développement Angus (SDA) and inaugurated in 2012, I came across an image of the building that had preceded it there, just by walking around on Google Street View and observing the evolution of the street corner over time.

I was struck by the contrast. Before its demolition, the building on the corner was home to various small businesses right up until 2008, counting among them Studio XXX, an erotic cabaret that offered services like a peep-show and private booths for XXX movies and full contact dances. Basically, the building was primarily dedicated to the sex industry.

What immediately and organically came to mind was a desire to know what had caused such a transformation of the intersection. What forces had come into play to bring about this change in the neighbourhood, and who were the main actors in this transformation? What positions did these actors – the arts institutions, the media, the municipality, the real estate developers, the community groups, the state – occupy in the history of this “revitalization” of the neighborhood? And who benefits from this change?

AG-MD: When you did your research, what did you discover about the consultation process in terms of the transformation of this area? Were there stakeholders who were for or against the demolition and the new project? How did this process unfold?

AM: All I found in the City of Montreal’s Archives about the demolition of the old building was a resolution passed in 2006 at the City Council to expropriate (with compensation) the tenants of the building of which Studio XXX was a part. There was apparently no publication consultation on the demolition.

However, since the initial project of the 2-22 proposed the construction of a building exceeding the height limit allowed by the Urban Plan of the City of Montreal, there had to be a public consultation in order to get the necessary authorization before proceeding. It was at this time that the different interests of the people and organizations implicated could be identified. The various stakeholders were very divided.

In general, arts and culture organizations, especially those involved in the project and who would gain access to the property through the 2-22, were absolutely supportive of its development. It would provide security, access to a work and dissemination space almost impossible to find otherwise. This is a real issue in the arts and culture community, there’s no denying it. Access to space is very difficult to find for artists and distributors, who have not been spared by the rent increases related to gentrification. So having a permanent venue in the middle of the Quartier des spectacles was very attractive for organizations like VOX.

On the other hand, heritage and community organizations were less enthusiastic about the project. Heritage organizations were concerned that the SDA’s projects would not integrate well with the historical character of the neighbourhood, especially the sister project of the 2-22, the Quadrilatère Saint-Laurent [today known as Square St-Laurent]. This second component notably threatened to do away with Café Cléopâtre, but they resisted and refused to be expropriated. The case made its way to court.1

Many community organizations opposed the project or voiced reservations – because there is important nuance to this: organizations recognized that there was some value in the project, but they also saw risks, primarily for neighbourhood residents. Several organizations, like Stella2, wrote a brief to express their concerns.3

Essentially, what they proposed was to be a key stakeholder in the project, to be local actors in the building project of the 2-22, to have a say, to participate in the development of the project, to be consulted. They extended a hand to the project developers, but it was not well received.

Stella had been on the Main for eight years and so knew the neighbourhood very well. What’s more, they had been among the many people and organizations who had to relocate due to poor building conditions. They recognized that it was a neighbourhood that needed care, love, money, and development, but not in the way proposed by the SDA, the company executing the 2-22 project.

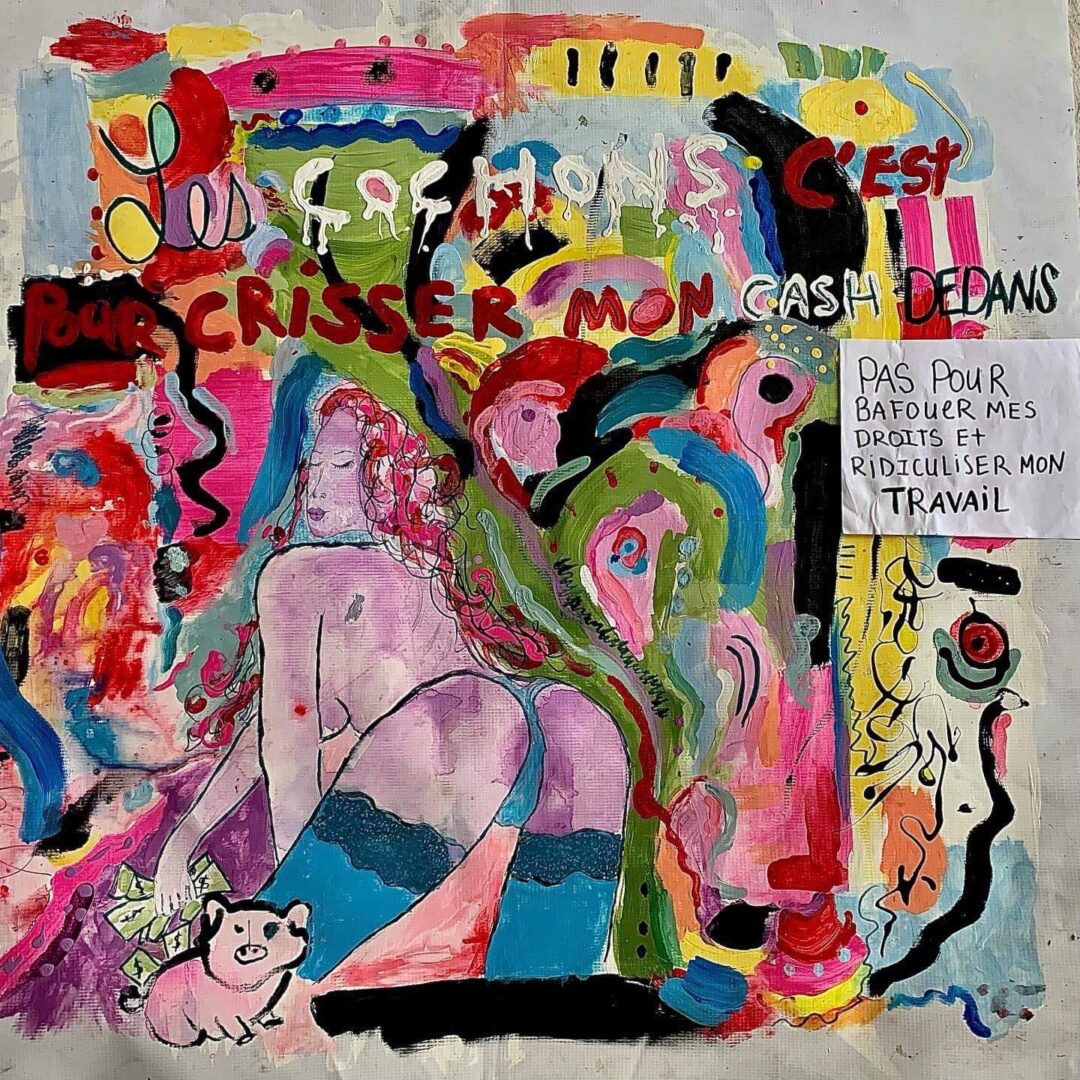

Another thing that I learned reading the brief from Stella was that during the time that they were located on Saint-Laurent Boulevard, they had a display window and organized exhibitions, mainly about sex work and the history of the Red Light district.

This highlights an important question when we’re talking about cultural policy: what is defined as belonging to the cultural sector, and what kind of practices are given visibility? For example, material related to sex work, like the window exhibitions presented by Stella, would not so easily be found on the walls of the 2-22 because the “guardians of culture” have judged it immoral. This is evidenced by the bylaws of the building. They are not welcome in exhibition spaces, in spaces of cultural diffusion, because for some, these forms of expressions are taboo. But with the choice to avoid offence, we push them to the margins. It’s curious because historically, sex work and the arts have had an intimate relationship.

What I found also such a shame about this whole process is that by displacing the communities that live in a place, you really break the link between those communities and their sites of work, you disrupt their legacy by pushing them completely out of the center, out of touch with their history. This prevents the ongoing transmission of the place-based histories of these communities of practice. The conversations with SWAC made this very clear. It’s really hard to cultivate the collective memory of a place, of a community’s culture, when the connections are so fractured on so many levels by gentrification.

Another interesting thing about the brief produced by Stella is that they had compiled a list of negative impacts already observed in the area since its rezoning, even before the 2-22 project was presented to the public. During the period when the gentrification process was in its early stages, as the Quartier des spectacles was first being constructed, they did a field study which showed that not only were sex workers (SWers) already being displaced to other areas, but at the time there were increasing police inspections, constant police presence in the area, and an increasing number of fines being given to “undesirables”. This resulted, as with the demolition of Studio XXX, in job loss, the loss of SWers networks, and an erasure of their collective memory in the neighbourhood. This was a very live issue even before the 2-22 came along.

AG: In the new project, did you find rationale for the need to revitalize the area?

AM: On their website, the SDA uses a number of catchphrases and images to introduce their projects, and one term that comes up a lot is “revitalize,” in this case to “revitalize through culture”.4 It really gives expression to the phenomenon that I have been investigating while working on this project. What it says is that the neighbourhood was “dead” and they needed to revive it by replacing the local culture with a different, more controlled and profitable one.

MD: They saw it as dead, but it certainly wasn’t. There was activity, but they didn’t acknowledge it.

AM: Yes exactly. Often they were invisibilized or illicit activities, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t exist. Actually, in an interview, Gérald Tremblay, the mayor of the City of Montreal at the time of the construction of the 2-22, said that he was sick of seeing boarded up buildings. There’s this desire to make the area profitable at all costs, but not to provide access to housing, to health clinics or things that could really serve the population. You can’t just make art spaces, offices, entertainment and consumer spaces; to allow people to really inhabit a place, to live well, you have to diversify its activities.

AG-MD: As part of your process, you conducted an interview with several SWers, including activists with SWAC. What emerged from this about the relationship between gentrification and sex work?

AM: I think that question is best answered by the collective itself. So I’ll share some of the highlights.

What stood out to me the most in the conversation was that gentrification as a phenomenon is not just about space. It starts with the displacement of communities, yes, but the effects go beyond that. Particularly for SWers, there are the psychological and relational impacts, since displacement affects their ability to offer mutual support.

What’s so impressive is that despite this, SWers find ways to rebuild their connections, to develop new ways to support each other, to be there for each other, and to share the resources they need to do their work. I think that’s really what SWAC is all about.

Something else that often came up in the conversation, is that the more that spaces dedicated to sex work are destroyed, the more isolated SWers find themselves, everybody working alone. This makes solidarity and collective struggle more difficult, but can’t stop it completely; efforts always persist!

These displacements also underline the importance of common spaces, connected to shared professional activities. We can see that it’s in these spaces where exchange and sharing is possible that bonds can develop that transform the spaces into sanctuaries.

A critical issue is that so long as sex work remains a criminalized activity, there is a limit to the safety that sex workers can find in their places of work. They make their own safety, showing incredible resilience despite the ever-increasing urban transformation that hinders their search for security.

What also came up during the exchange is that in Quartier des spectacles, there is a vicious and ironic process of relocating working communities and then taking advantage of their language, their symbols, their tools of representations, to promote the sanitized new district and increase its value. For example, the glass façade of the 2-22 building is apparently a reference to the dancers who stripped in the windows of the Red Light District. The symbolics of these communities are being exploited, while they are denied access to their work, are capitalized upon via the criminalization of their work or simply by their legal exclusion, as we saw with the 2-22.

In addition, by gentrifying and displacing communities and shutting down their places of work, we also reduce their access to services they need. For example, Stella was forced to relocate because of gentrification, which has had a negative impact on SWers’ ability to access the essential, front-line services Stella provides.

I’ll finish by saying that overall, gentrification invisibilizes all these marginalized practices by pushing them further and further from the centre towards more isolated areas, removed from the sight of the rest of society. This puts people in danger, because the more invisible they are, the more at risk they are for violence and abuse. It is a profoundly disturbing impact of gentrification. It’s violence sanctioned by the authorities.

AG-MD: Are you the only artist who has been interested in the building that predates the 2-22?

AM: I did find other artists who were interested in it and wanted to document the existence of the peep show, before it was demolished.

One is Mia Donovan, a photographer and documentary filmmaker who spent her early career documenting the sex work milieu. During that time, she made a series of photographs with SWers at the former Studio XXX.5 As far as I know, these are some of the only images we have of the interior of the space before its demolition.

Another is Angela Grauerholz, also a visual artist, who shot a video of the intersection in 2005. At that time, we could see an overhead projection of two dancers in the window of Studio XXX, on the corner of Saint-Laurent and Sainte-Catherine.

These artists have documented the existence of these SWers by foregrounding them in their places of work. They were really interested in the physicality, the incarnate presence of the bodies of the SWers in those spaces, and not just the building itself. That made a big impression on me. It’s my hope to delve into the connections, of which there are many, between sex work and the arts. Many sex workers make art and many artists do sex work. I think we have a lot to learn and share.

dans le souffle de c. was presented at VOX Contemporary Image Center, from September 9th to December 3rd 2022 as part of the exhibition The Radical Imaginary II: Reclaiming Value.

You can find other documentary resources that informed the project on its web counterpart: https://tinyurl.com/danslesoufledec

1. To learn more about the fight for Café Cléopâtre: Wikipedia. (s.d). Café Cléopâtre, from https://tinyurl.com/cafecleopatre ↩

2. Stella is a community-based organization that seeks to improve quality of life for sex workers, to raise awareness and to educate society at large about the realities and forms of sex work so that sex workers have equal rights to health and safety as the rest of the population. For more information see: https://chezstella.org/ ↩

3. To read the brief produced by Stella: Stella. (2009). Mémoire sur la requalification du Quartier des spectacles, from https://tinyurl.com/quartierdesspectacles ↩

4. Société de développement Angus. (n.d.). Le 2-22, from https://tinyurl.com/le2-22saintlaurent ↩

5. This photo series was presented at Monument National in 2008 as part of the exhibition Le Coin produced by UMA, la Maison de l’image et de la photographie. The three selected artists were invited to document the intersection of St-Laurent and St-Catherine streets, on the cusp of its transformation. To learn more about this exhibition: UMA, la Maison de l’image et de la photographie. (2008). Le Coin, from http://www.umamontreal.com/lecoin/ ↩

Open Letter La Paix des Femmes

Open Letter in Reaction to

La Paix Des Femmes

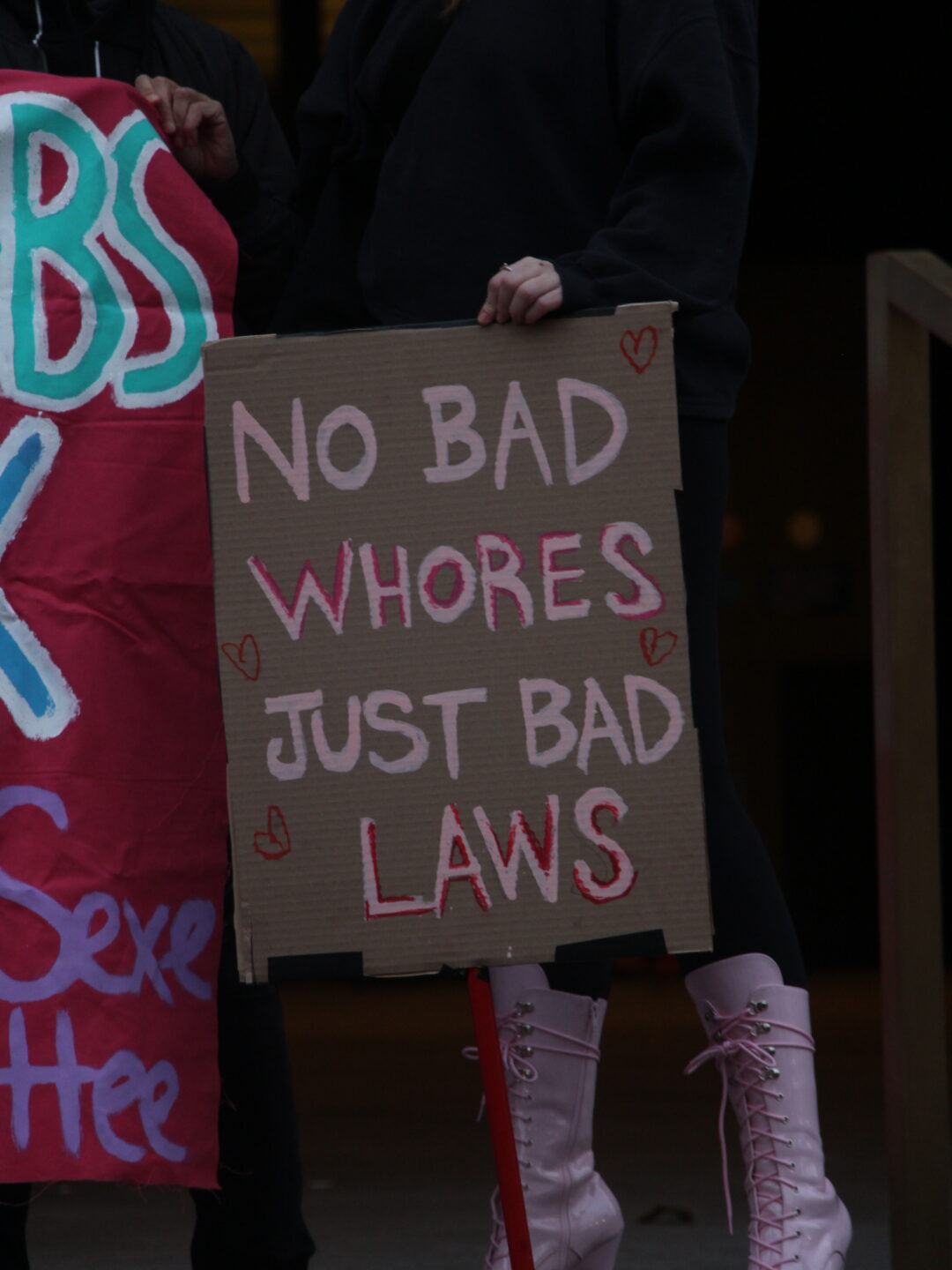

Maxime Holliday, Translated by Julia Thomas

La paix des femmes is a play written by author Véronique Côté in collaboration with abolitionist activist Martine B. Côté. Together, they sign this work as well as a related essay (Faire Corps), both published by Atelier 10 editions. The play was presented in Quebec City at La Bordée in the fall of 2022. One month before the performances began, Maxime Holliday, activist from the Sex Work Autonomous Committee (SWAC), published this open letter to denounce the play which, according to her, makes a crude, alarmist and dangerous representation of sex work. Speaking directly to the author, Maxime called for more diverse voices from the community to be brought into the play, thereby attempting to clarify (again) the difference between consensual exchange of sexual services and sexual exploitation. Following the distribution of the letter, a dialogue between Maxime and Véronique led to the latter withdrawing a line from the play and proposing that part of the written exchange between the two women be printed and displayed in the theater hall. During the first performance, pro-sex work activists interrupted, standing and carrying red umbrellas, to chant “my work, my choice” before leaving the room.

Hi Véronique,

I’m writing to you today to discuss your play, La Paix des femmes. To start, I want to say I have much respect for your body of work – both the literary and the theatrical. You directed me twice during my time at CÉGEP, and I adored you. I will never forget when République: un abécédaire populaire came out, and you canceled our rehearsal to take us to the cinema to see it. I thought it was so beautiful, so rad, I promised myself I would always live up to the energy and passion you shared with us. I read S’appartenir(e) and La vie habitable. I saw you in Mois d’Août, Osage County and Laurier Station: 1000 répliques pour dire je t’aime. I went to see Scalpée because you were the director. I was never disappointed. You are right and you have a gift for touching people.

When I heard from friends earlier this summer about La Paix des femmes, I was excited. Because prostitution is a subject I’m passionate about and one that I know well. A little background on my life – after CÉGEP I did a bachelor’s degree, traveled, worked in restaurants and bars, and started playing music. I got a second college diploma and moved alone into a beautiful apartment with an old, adopted cat. During the pandemic, I meditated, worked on art projects, met a wonderful person with whom I share a deep, loving relationship to this day, and moved to Montreal. I ended my career in food service after being hostile with two customers in the same week. I was stretched to the max after eight years in the industry and knew myself well enough to pull back before I snapped. In 2021 I started working at an erotic massage parlour, which I still do today, as well as working from time to time as a nude dancer in bars. I love it. My life is balanced and dynamic. I am a curious, politically engaged, caring person. I make art with my friends, performances and I take care of myself, my family and those around me. I read Martine Delvaux and Judith Lussier and listen to Angèle Arsenault.

My friends are aware of my work in the sex industry, so I quickly heard about your play being published. I was told it was a dialogue between an abolitionist and a pro-sex-work scholar. I was told it was nuanced and written from multiple perspectives. I was skeptical but eager to read it because you wrote it. That is until my mother wielded your text at me to convince me to stop doing sex work. My poor, terrified mother, who has brutally invalidated me since I first wrote to her almost a year ago telling her about my work. My own mother, so freaked out that she can’t even hear or listen, much less trust me when I try to tell her about my experience. My mom emailing me your play. And my stomach in knots because, at that moment, I realize that the play confirms all her most sordid fears about my existence. At first, I’m so exasperated I tell myself I won’t read it. Anyway, she has refused to read anything I send her for a year. But what I needed the most was to be considered and heard. So I chose to open a dialogue by offering her a reading in exchange for a reading, which she eventually accepted.

So I read your play. While camping in the Jacques-Cartier Valley with my lover. I understand that your writing comes from a feminist impulse, a place of benevolent sisterhood, but I find this text hurts. Because it’s not a dialogue. It’s a lynching that rehashes all kinds of clichés about sex work in which exploitation, human trafficking and prostitution are all the same. The conversation occurs between a young woman (Alice) who decides to brutally confront Isabelle, the former feminist studies teacher of her sister (Lea), dead of an overdose six months after having started to prostitute herself. Alice blames Isabelle and the feminism she upholds for having caused her sister’s death, relying on an aggressive and dismissive abolitionist rationale. The character of Isabelle, who supposedly bears the pro-sex work argument, is discredited in the blurb on the back cover and tends to make dubious statements. She keeps waving “agency” as the solitary white flag to defend sex work in her discussions. And yet it is this same agency that we lose when she suggests that, as sex workers, “it is all we have left “1 and “they can’t take that away [from us].”2 Such claims strip sex workers of our agency, victimizing us and painting a bleak portrait of our reality. The story of Lea, dead after being recruited into a trafficking ring, inspired by the real lives of women who have been victims of coercion, extortion, abuse, and assault – is valid and alarming. We do need to talk about this reality, to denounce it. To shout out loud that as women in a misogynist and oppressive patriarchal system, we have lived and continue to live through appalling sexual violence. In this system, violence, as you say, is everywhere. It is intersectional. But I am so angry that these stories of exploitation are systematically used to represent prostitution in general, invalidating all those whose experience of sex work is ordinary or even straight-up positive. Ordinary experiences generally aren’t reported publicly or are labeled as isolated cases, creating an unbalanced and distorted image of our lives. Because If we are shown reports from Radio-Canada on “sugar babies” being manipulated and abused or women getting assaulted and killed, they also need to show us the story of the 45-year-old woman who has quietly worked for 20 years, and those for whom sex work is a means for empowerment and a good life.

Clarifying the difference between the consensual exchange of services and sexual exploitation, once and for all, would allow us to better combat pimps and fight to curb human trafficking more effectively. At the same time, SWers would benefit from improved working conditions to organize themselves and ensure their health and safety at work. Because this is indeed an intense job, and it is not made for everyone. The cliché of quick and easy money is totally absurd. Sex work is work. There are many security challenges, and strong relational, communication, and entrepreneurial skills are a requirement. It seems evident to me that all the energy used to discredit SWers and try to make them disappear would be much better used to help them obtain better tools for their trade and establish an empowering and safe social and legal framework. You infantilize a person when you suggest you are better at making choices about her life than she is. The worldwide abolition of prostitution is a legal and theoretical fable that only works on paper. I fail to see how the state could control the individual agency of SWers and their bodies without falling into repression and totalitarianism. And while it is indeed urgent to find ways to help women in extreme poverty who prostitute themselves to survive, it must be recognized that social and economic precarity would persist even if prostitution were made wholly illegal and/or magically disappeared. We can only make the lives of sex workers more difficult by stigmatizing them and working against them and their clients. Like with abortion, which can never be totally eradicated but can undoubtedly be dangerous when practiced under the wrong conditions, I believe that prostitution in Canada should be decriminalized 3 ; to allow SWers to self-organize according to their needs, which they know best, and create shared spaces, training opportunities, and unions to foster the improvement of their working conditions.

La Paix des femmes, unfortunately, still contributes to the deliberate conflation of consensual exchanges of voluntary sexual services with human trafficking. Because if I understand correctly, the play was written based on only two testimonials (K. and C., thanked at the end of the book)? It seems that a sample of two individuals is not enough to get an accurate idea of how a whole environment, which one has not directly experienced, works. The contribution of your friend Martine B. Côté, student researcher and abolitionist activist who has worked with victims of exploitation, was no doubt highly relevant. If the play, and the attached essay, claimed to be about exploitation and sex trafficking, that would be fine. But because the works claim to speak “for women and against the system that exploits them” 4 about the concept of prostitution in general, I find the gratuitously violent and shocking images conveyed in the play to be shamelessly ridiculous and crude. 5

It seems to me that this willingness to see using one’s body in a sexual way as automatically dangerous, painful, dirty, dishonourable, and shameful is a throwback to the outdated Catholic thinking that once controlled sexual morality. Suppose we believe today that women have a right to their bodily autonomy and sexual freedom. Why should “dislocating your jaw from giving blowjobs”6 (which already strikes me as either a horrible experience of sexual violence or a stylistic exaggeration but not a frequent consequence of practicing fellatio) be a worse scenario than destroying your lungs by breathing in chemicals in a factory, blowing out your vertebrae by lifting people to wash them in a hospital or ravaging your mental health as an overworked teacher in an elementary school? The patriarchal capitalist system exerts economic and social pressure and dominance on all women and all workers, regardless of their field. I am trying to demonstrate how our system threatens the physical and psychological health of so many of us. The working conditions of migrant people are often compared to modern slavery. The average household is being held in a chokehold by the ever-increasing cost of living. In this context, prostitution can easily be, for some people, the most practical and appealing way to pay for rent and groceries. It can also be an appealing occupation simply because sexuality and social work (because I assure you that sometimes we do act as social workers in lingerie) interest and stimulate us more than working in a hardware store, making sushi or being an administrative assistant in a production company.

For almost two years, I have worked with ordinary women, self-employed workers in the industry. Students, mothers, sisters, lovers, nurses, graphic designers, musicians, cashiers. For some, it’s a side job; for others it’s full-time. In the staff room, we tell each other our stories, we talk about our clients. Sometimes, we work on our computers in silence while waiting for appointments, sometimes, we share snacks and laugh loudly. In the strip club dressing room, we chat with the bouncer while putting on deodorant and take dinner breaks. We work where we choose to work and on good days, we earn a very good salary. I have many friends who work online, others who are independent escorts. I know a male escort for women too. Everyone, regardless of gender, needs physical contact. You’d be surprised how many people around us use these services but remain anonymous for fear of legal repercussions, stigma and shame.

Why is it still so inconceivable today that it is not necessarily humiliating and traumatic for a woman to get paid to dance naked or offer sexual services? Why is it automatically offensive to imagine a woman performing multiple blowjobs in one day? As far as I’m concerned, the end result of the feminist sexual revolution is to recognize the traumas we have lived through and to give ourselves the means, however diverse, to heal from them. Our great-grandmothers and grandmothers, required to sexually satisfy their husbands and produce children even when they didn’t want to. Our grandmothers, our mothers, and we live in a society where scientific research on female sexual organs is woefully behind that of male sexual organs. Our mothers, sisters, daughters, and we ourselves, who still have to research contraception for ourselves and fear that abortion rights will be revoked here too. Can we acknowledge our sexual trauma and work together to heal and liberate ourselves, all while respecting each other’s pace? Live and let live. I understand and appreciate that some women may feel repulsed and threatened by the kind of sexuality instilled in us by the hetero-patriarchal system. Because this model is indeed abusive, restrictive, and threatening to us. But all while recognizing this, could we also be capable of caring for each other inclusively and respectfully, allowing each of us the freedom to manage the use of our body as we see fit? If I enjoy offering sex, paid or free, with my own body, which I take care of and which belongs to me, who am I hurting? My body continues to belong to me after my workday. I ride my bike with it, I pet my cat with it, I eat with it, I listen to music that I like with it, I work out with it, I have a glass of wine with it. I have sold a service but not my body. I find that getting paid to perform femininity and heteronormative sexuality is also a way to infiltrate the institution to bring it down from within. Because it recognizes that women never owe men anything. No sexual and/or relational work. No care work and no extra mental workload. That there are people paid to offer this kind of service, as far as I’m concerned, contributes to a return of power. To avoid the exploitation insidiously victimizing all of us in societies that teach us to fulfill men’s needs for free because “it is due to them.”

Coming back to the play, I also want to mention the things I liked: first of all, the fact that it raises questions about bodily autonomy in the context of egg donation. This is a topic I knew little about until recently, and it is pertinent to reflect on. And secondly, I liked how the client archetype was humanized through the character of Max. Well, what I remember is that the couple doesn’t communicate very well and that Max betrayed his girlfriend. He’s not the hero of the story, let’s say. But I’ll take that as a jumping-off point to say a word about clients. Before working in the field, I thought clients would all be big drunk macho jerks or old perverts. In the end, those clients do exist, but they are not the majority. And just like massage therapists, osteopaths, or tattoo artists, after an unpleasant appointment with a bad client, I make a note to myself not to take that client anymore. In reality, the majority of my regular clients are ordinary people. Neuro-divergent people, people with disabilities, recently divorced dads, insecure young people, old widowers, veterans, terminally ill men, and newcomers who have difficulty meeting someone because of cultural and language barriers. People with human needs. People who want to cuddle, who want to come and be validated. The patriarchy harms male-socialized people too. Everyone needs to be educated and to heal. I believe in the capacity of people and societies to learn from their mistakes and to improve themselves. I think there are many ways to change people’s behaviour and stop exploitation and violence against women. But just as I don’t think banning the sale or purchase of sex teaches men to respect and care for women or themselves, I don’t believe that it is prostitution that prevents women from having the same privileges as men. Misogyny is everywhere. In the price of feminine-gendered products, fatphobia, systemic racism and rape culture. It is within our intimate relationships and marriages. It is in the justice system, deficient when it comes to defending survivors of sexual abuse. Violence exists far beyond the concept of prostitution, and I think the day that society respects and cares for prostitutes as for any other woman, we will all have won something.

You carry your feminist fight through your art, and so do I. There are many feminisms and truths, yes. But to read comments like Francine Pelletier’s, quoted at the end of your play, which suggest that women are being inconsistent by choosing “to look like dolls”7 or “choosing to stay home and raise their children”8 revolts me. To think that women cannot perform an ultra-feminine gender identity or decide to dedicate their lives to their children at the risk of harming the feminist cause is binary and outdated feminist thinking. It still puts all the pressure on women, as if society will always hold it against them no matter their choice. As for my feminism, I update it constantly, and I fight for it on all fronts. In my personal and professional life. On the streets, in my bed, and on social networks. My songs are about our emancipation, and I use my workplaces as a space for direct intervention. I work with my legs, armpits, hairy pubis, shaved head, and sometimes long nails and artificial lashes. I feel beautiful and whole. I always say what I think. I am gentle and tender, but I never overstep my boundaries: I am firm in enforcing them. I resist, educate, and I cum. Sometimes at work and always in my intimate life. I cum. Because I am a woman and I belong to myself. Because I am a rigorous intellectual, a passionate artist, a faithful friend, a committed lover, a staunch feminist, a caring sister and a gifted and proud sex worker. If I am accused of inconsistency, I would say it is more a matter of freedom. Cultivated and nurtured through adversity.

Reading your play, Véronique, I felt uncomfortable and bitter. It upsets me even more to think that the play will be presented in September at La Bordée. I can’t see how presenting this work will do anyone any good. But I can see how it will hurt many people. This play exudes fear, helplessness, rage, and pain but does not offer real solutions to improve anyone’s well-being. This play conveys all sorts of feelings that I share facing the injustices and violence experienced by women. Still, it approaches this complex subject in such a superficial and one-sided way that its impact is already being felt negatively in my personal life, as it will inevitably be felt in those of my friends and colleagues. Even if I do not share your opinions on the future of prostitution, I would like to highlight all the good you and Martine are undoubtedly doing by listening to and helping victims of sexual violence get out of violent situations and rebuild their lives. I sincerely thank you for being there for these women, but I also urge you to consider the impact a play like La Paix des femmes can have on the collective imagination. For if the three of us are initiated into the subject of prostitution and human trafficking, the average person is entirely ignorant of the reality and issues involved. To present such an alarmist and unnuanced work will have, in my opinion, damaging moral repercussions on the cause of SWers and women in prostitution, particularly in Quebec City and the surrounding area. Therefore, I am addressing this letter to you, Véronique, and the entire production team to ask you to act by opening a healthy and diverse dialogue with our SWers community and integrating other points of view and informative resources from our community into the presentation of your play. We really need safe working conditions, to be listened to, consideration, inclusion, justice and respect.

I am sending you this letter through the SWAC, a self-governed organization in which I am an activist, to maintain my anonymity. Thank you for respecting my anonymity, even though you may have recognized me by the very personal tone of my letter.

Thank you for reading my words.

In the hope of awakening reflection and compassion.

Maxime Holliday

25 juillet 2022

1. Véronique Côté. (2021). La paix des femmes, p. 90 ↩

2. SAME ↩

3. Like in a certain area of Australia, in New-Zealand and in Belgium since June 2022. ↩

4. Véronique Côté. (2021). Faire corps, back cover ↩

5. I want to reiterate that I speak from my experiences and those of my colleagues and whore friends. I am in no way discrediting the experiences of the women who have spoken to you, which are also very real and valid. ↩

6. Véronique Côté. (2021). La paix des femmes, p. 90↩

7. Francine Pelletier. (2018).Le corps d’une femme, Le Devoir quoted in Véronique Côté. (2021). La paix des femmes, p. 127 ↩

8. SAME ↩

Poems – By Percevale

Poems

Percevale

Those poems have originally been written in french. Translating poetry is a hard task and is here to inspire and try to represent the artist’s words and intentions. The french poems have subtleties that can only be understood in that language.

I.

prostitution is not

a contract

it’s not a husband

I don’t have a ring on it

I do it like this

with good sex

with good faith

before I pick up my cash

and tell them

”see ya”

give me some cash

so that I can buy in return

something to charm

all the men I like

I accept all gifts

even impersonal ones

everyone loves wine

and I

make poems out of it

I don’t like jewelry

but when I receive it

from you

I find myself looking elegant

and it excites me strangely

I fall in love

3 times a day

for less than thirty minutes

and I know nothing

about love

II.

they laugh at my jokes

with a good heart

half nostalgic half happy

my cold-hearted charitable

old men

who will never tell their wives

and I

made the choice to enjoy it

I find it poetic

I even find it quite comic

and I

have decided

that I can take what

it generates

it’s like an

actress’s job

psychologist’s,

of a penis not too steady

on the money intakes

like a job that cuts you in two

with a baseball bat

that brings you bread on

the table

that you can do everywhere

on the map

when you’re

whore-able

III.

i just took off all of

my clothes

just my

earrings left

but I only wore one

today

I’m sleeping at the whorehouse tonight

tomorrow it’s time

I hope I don’t feel anything

(I just want to feel you)

I take a sniff on

my arm

it smells like your sweat

a little bit

we’re not too big on

showers when

we’re together

huh

here I wash up after

every guest

the rooms stink

of condoms

cheap perfume and spunk

I think of you who

earlier said to me

“I love you”

for the first time

life is damn beautiful.

IV.

the girls are whining about

no customers

putting on makeup in the meantime

they tell me to comb

my hair

that self-care is important

I just want to be proud like

a boat

that has no human

to get on board

all I care about is

to not sink

I don’t care which way

the current goes

V.

the motels will be

kingdoms

like the old back bench of the

car

the beds will be temples

and cigarettes

medicine

in our stinking mouths of

beings

who kiss each other without rest

who eat with their mouths open

and laughing

all the time

Beyond pride : A Call for Queer and Whore Solidarity

Beyond Pride

A Call for Queer and Whore Solidarity

Adore Goldman, Cyprine & Melina May

This text was written in the summer of 2022 and distributed at the Pride Community Day on August 5th and at the Anarchist Book Fair on August 6th, as the 24th edition of the International AIDS Conference in Montreal was ending.

Among the moral attacks that Pride is regularly subjected to – outside and within our communities – one criticism in particular seems indestructible: Pride is definitely an event that is too sexual. Indeed, from fetish outfits to drag parades to public displays of physical affection, they say that the sexuality queers exhibit is too present, too loud, too vulgar, too disturbing. Pride is a space of hypersexualized bodies, and those who participate are inveterate fuckers without dignity.

At the same time, this critique reveals the biases of those who formulate it: from a cisgender and bourgeois perspective, sex should be private, practiced in the bedroom, well away from the public eye. But on the other hand, it reveals the importance of sex in our communities. While this criticism misses the political dimension of sex, it is right about one thing: Pride and queer communities have put sexuality at the forefront of their political agenda. And that’s a good thing.

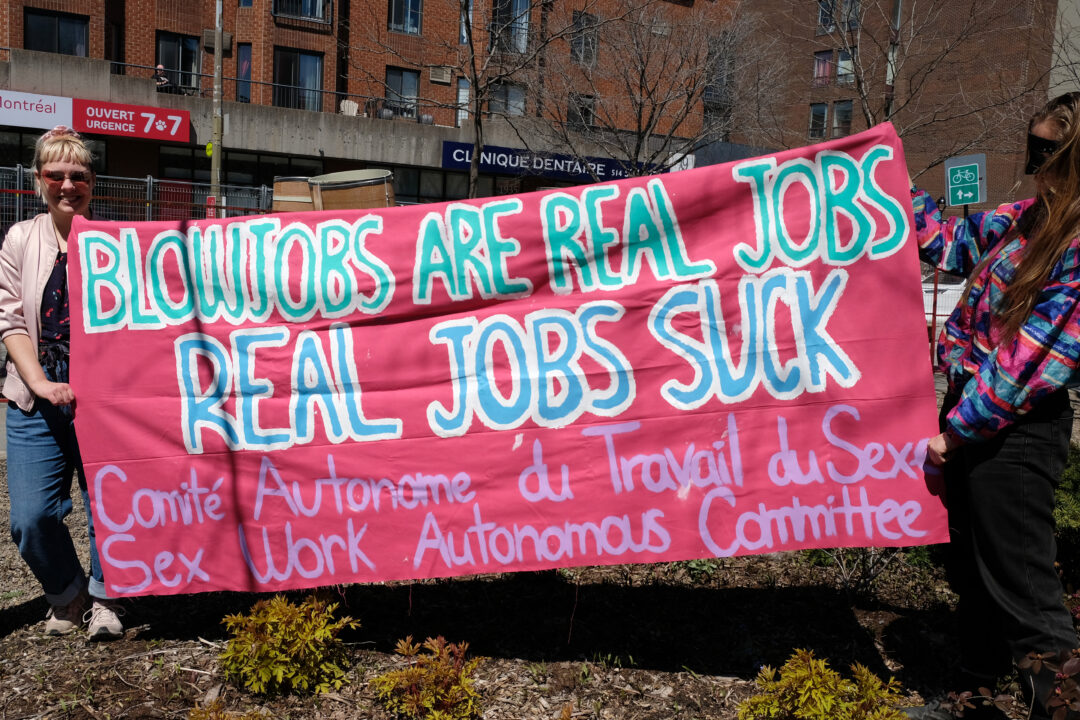

It is from these observations that we can question the place of sex workers (SWers) within queer protests and community spaces like Pride. If queers have in fact been associated with a movement of liberation and recognition of sexual minorities, what about the place of SWers? If sex is so present in our communities, and in a much deeper way than just “party sex”, how do those who practice it on a daily basis, those who are experts in it, the SWers, relate to the queer liberation project? As SWAC activists, we took the opportunity of Pride 2022 to remind our queer friends of some avenues of solidarity between our groups, and the need for a political position in favor of decriminalization of sex work in queer events such as Pride.

Queer and SWers, a Common History, a Liberation Together!

Queers and SWers share a collective history of struggle. Pride and its street parade, celebrating all gender and sexual minorities, takes place every year in homage to the Stonewall riots that took place in June 1969. Without re-telling this story that has become ultra famous (perhaps even too famous, to the point of making it year 0 of the gay rights movement), it is important to remember that sex workers occupied a central place in the so-called “deviant” sexual communities, and were precisely those who frequented the Stonewall Inn. Indeed, many queer and trans people relied on sex work for their survival. Above all, the Stonewall riots were particularly significant in that they established a power relationship with the police. It is precisely because of those who were most exposed to police violence that this rebellion could take place with such force. At the forefront of the systemic police criminalization were homosexuals, trans people, queers, and whores. All of these people were mixed together in underground and nocturnal spaces in the metropolis, creating counter-cultures and building parallel economies. Selling sexual services was the basis for the survival of many. This is not to say that all sexual minorities were doing sex work, nor that SWers were a homogeneous and fixed group always standing alongside other minorities. Rather, we would like to emphasize the cross-cutting nature of sex work in these spaces. Most importantly, regular police raids targeted SWers bodies, regarding them as dirty and unwanted, in the same light as queer bodies. It is no coincidence that these bodies moved through the same spaces, creating affinities and resisting violence together. This shared history of criminalization continues today; worldwide, 72 countries criminalize homosexuality, while the majority of the world’s countries have not yet decriminalized sex work (with the exception of New Zealand, Belgium and parts of Australia). In other words, SWers, like other dissidents of the cis-heteropatriarchal order, have been and are still subjected to state and police violence. Another important point is that the homophobic treatment of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s gave rise to a pathologized image of gay men as vessels of disease, infectious bodies whose sexuality was inherently dangerous. In the same way, our sex-working bodies are seen as dirty and dangerous spaces, which only the most hygienic policies can deal with. Thus, one model of “management” of prostitution, called regulationist, aims to politically regulate the practice of sex work through sustained health control. This only feeds into this representation of a degraded and unhealthy body. Like gay men during the AIDS crisis, we are also constantly brought back to the idea of an absence of “purity” in our practices, and our identities are in themselves constant medical and social danger. Recent studies have shown that a significant proportion of trans women, who have been completely ignored by statistics until now, are affected by AIDS, but receive little care, while in some countries they simply do not have access to the latest treatments. In other cases, they have to choose between their hormone therapy and HIV treatment because they are incompatible. The issue of health and vulnerability has thus linked both queer and SWer communities since the 1980s (and again, these communities can’t even be referred as two distinct groups). Finally, Pride has become an increasingly well-known event in the last few years, and the price of this “mainstreaming” is high. Indeed, few remember Pride as a moment of celebration of the queer and SWers anti-capitalist force, spitting and rebelling against the police and the normative social order. The celebration of sexual diversity as a revolutionary political project has gradually been transformed into a process of institutionalizing homosexuality under the paradigm of tolerance, with a focus on the integration or even assimilation of cis-gay men into the cis-capitalist system. The issue of gay marriage, among others, seems to have taken on a disproportionate role in the political discussion. Like others1, we think this quest for equality is dangerous in many ways; by claiming marriage as an object of dignity for sexual minorities, the norms between good and bad sex crystallize and make us, SWers, lower-class subjects. It also trivializes whorephobia within queer circles, previously allies of our struggles. If marriage becomes the promise of political dignity, what about those who continue to trouble this institution, SWers for instance? Now, if it’s about being in a couple, having an adopted child, and a house on credit for two generations, how does that differ from the aspirations of a capitalist society based on the exploitation of the weak? Thus, queers, as a critical force of the gender binary, and as a target of the state, must divest from this political turn that effectively excludes SWers, trans people, and all those who distance themselves from the project of social integration and assimilation. Moreover, the word “gay” has progressively replaced the word “queer”, and the promotional images of Prides on an international scale are full of thin, able-bodied, white, cis-gay men. Our project is more radical than that, and one only has to look back to the history of Stonewall to be reminded of that. If historically there are clear links between queers and sex work, it is interesting to ask why queers today practice sex work. There are several reasons, and the list is far from exhaustive:-

- First of all, gender minorities around the world face material precariousness. The subject is not new, and there is a whole section of materialist feminists, and in particular those with a focus on Third World and are very critical of “development”, who have succeeded in formulating a fundamental concept to highlight this reality: the feminization of poverty. This means that economically, gender minorities systematically own less land, are less likely to be property owners, and receive fewer economic benefits than their cis male counterparts. Precariousness, in this sense, is not just bumping up against the glass ceiling, but is a whole system, from lack of guidance at an early age, to lack of access to schools, to housing discrimination. This particularly affects poor and racialized minorities, for whom sex work may be one – if not the only – way to survive.

-

- Sex work is described by some minorities as a way of exercising with their peers. For trans women, for example, and trans women of color moreover, it represents a significant space in a society where their bodies are constantly rejected, denied, and treated as inferior. For those who transition physically, the costs of surgery and the lack of financial support pushes them to turn to sex work. Thus, “Monica Forrester, Jamie-Lee Hamilton, Mirha-Soleil Ross and Viviane Namaste argue that “a history of transsexuality is a history of prostitution,” contending that “the social enclaves that have historically enabled trans communities are predicated on the political struggles of trans sex workers, a category largely made up of women of color.”2

The Laid-off Workers of the Family

While the LG 4 movement has put forward the demand for marriage equality in recent decades, it is clear that these demands have served the interests of the middle class and the well-off more than those of poor queers, who are more affected by discrimination in hiring and profiling, including trans people who do not benefit from “passing”. As Peter Drucker states, while access to marriage may bring material benefits to the middle class, “for those most dependent on the welfare-state in countries such as Britain and the Netherlands, legal recognition of their partnerships can lead to cuts in benefits.”5 Embedding oneself in capitalist and heteropatriarchal institutions such as marriage has therefore been strongly criticized by the queer movement, particularly in terms of the number of resources invested in such campaigns.

It should be remembered that family as an institution is a site of capitalist accumulation. More precisely, it is one of the spaces where the reproduction of labor power takes place. When we talk about reproductive labor, we are not only talking about biological reproduction. It also includes all of the tasks necessary to produce workers who are physically able to work (for example, cooking a nutritious meal). This work is largely based on its gendered division within the family and society as a whole. Thus, the integration of gender binary is part of the capitalist discipline that is transmitted by parents through education and is essential to the process of capitalist accumulation. Even today, much of this work is done for free by women within the heterosexual family. And since queers deviate from the binary roles (male/female, dad/mom, productive/reproductive workers), they threaten the gendered division of labor and are further exploited. As Kay Gabriel affirms, “capital has “invented roles” for the social categories it abjects, and uses these as a lever of exploitation“.6

It is not surprising, after all, that the family is a particularly violent place for those who do not fit into the lines of binarity. One of its roles is to ensure that children integrate the capitalist gendered structure in order to be able to reproduce it in their turn. Even homoparental families are tolerated only if they do not challenge this state of affairs. Even though their rights have improved considerably in recent years, social expectations remain unchanged; it is important that the children of these unions do not deviate from the heterosexual norm and integrate the structure of gender.

According to Peter Drucker, the tolerance given to gays and lesbians in the 1970s and 1980s has only been possible by repressing gender dissident within their own lines.7 This allowed a certain class to benefit from the development of a gay market economy (and subsequently, its gentrification). The Société de développement commercial du Village, a gay neighborhood in Montreal, is a good example.